Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico Rain Garden

Location

Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico

The challenge

Over the past 40 years, some of Puerto Rico’s most extensive coral reefs have seen increased coral bleaching events and declines in live coral coverage. Reefs around Puerto Rico are seriously degraded, with the worst damage manifesting in reefs immediately offshore from large human populations (Warne et al. 2005). Nutrients and pathogens associated with untreated or poorly-treated wastewater have been linked to disease in both coral reefs and humans.

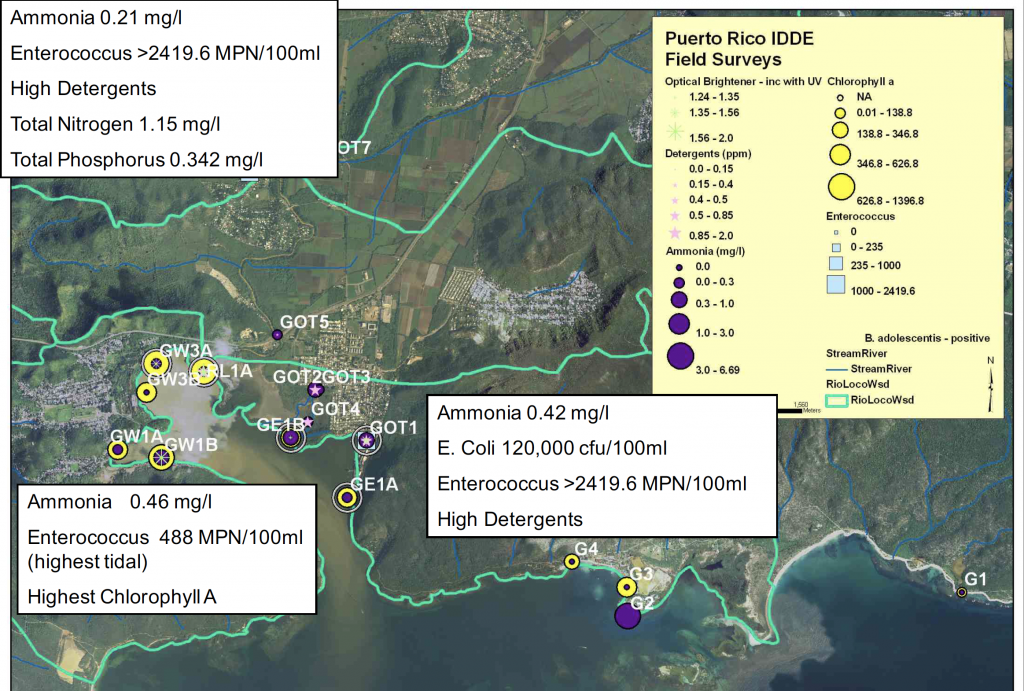

The Rio Loco watershed draining into Guánica Bay is 151 square miles, one of the largest in Puerto Rico. As this area has developed, runoff into the bay has increased nutrients and sediments to an estimated 5-10 times above natural levels (Ortiz-Zaya et al. 2005, Warne et al. 2005). As part of a larger, more comprehensive watershed assessment and pollution tracking project, nutrient pollution in Guánica Bay was determined to be coming primarily from sewage via wastewater treatment plants, leaky infrastructure, and sometimes a lack of sewage treatment systems. These nutrient inputs endanger the aquatic environment as well as the people using and visiting the Bay. About five percent of the residents in the town of Guánica are full time fishers, and several smaller communities in the area, including Papayo, Ensenada Honda and La Parguera, have historically been important fishing communities.

A map of Guánica Bay along the southern coast of Puerto Rico and the surrounding Rio Loco watershed identifies locations experiencing wastewater pollution. Indicators include ammonia, detergents, E. Coli, Enterococcus and Chlorophyll a. Photo © Ridge to Reefs and Protectores de Cuencas

A 27-room coastal hotel in Guánica Bay was identified as a source of sewage pollution during pollution tracking surveys that occurred as part of the implementation of the Guánica Watershed Plan. The Hotel’s unlined septic system was prone to regular overflows when overwhelmed by resident usage of toilets and showers. The coastal area adjacent to the hotel was found to have high levels of Chlorophyll a, ammonia, optical brighteners and indicator bacteria.

A wastewater plume in Guánica Bay and associated algal bloom. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

Actions taken

The hotel owners wanted to solve this problem and in collaboration with Ridge to Reefs, decided to construct a garden that could receive wastewater and drastically reduce its volume as well as remove or transform harmful components such as pathogens, nutrients and chemicals. Green Infrastructure uses natural ecosystem functions to provide additional treatment to septic tank discharge, enhancing contaminant removal and significantly reducing the volume of wastewater entering the Bay. For Hotel Parador Guánica 1929, effluent leaking from the septic system needed to be captured and slowed down to promote additional natural treatment.

Hotel Parador Guánica 1929. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

A vetiver grass rain garden with biochar soil amendment was used to capture effluent and increase nutrient removal. This type of system was chosen since the extensive root systems of vetiver grass rapidly take up water and nutrients, while biochar hosts beneficial soil microbes that remove nutrients from wastewater. Water leaves the vetiver grass through evapotranspiration, percolates through soil (undergoing further filtration), or enters underground pipes for discharge. Ridge to Reefs has been successful using other green infrastructure solutions from denitrifying bioreactors in the Chesapeake Bay to biofilters in American Samoa, which similarly use bacteria and natural materials to treat wastewater. At the Hotel, a rain garden with plants provided an additional aesthetic benefit, and can serve as an educational model for visitors to learn about green infrastructure solutions for wastewater treatment.

- The rain garden was sized to match the hotel’s peak water usage to prevent future overloading. Over 3 feet of soil was excavated and remediated with biochar and other carbon amendments. Belowground piping was installed, and vetiver grass was planted at the surface.

- The site was monitored for plant health, nutrient concentrations and water retention over several months until it was clear that the system was effectively treating the wastewater, based on plant growth and effluent nutrient samples. Samples were sent to University of Maryland’s Horn Point Laboratory for nutrient analysis and averaged over 50% removal for both nitrogen and phosphorus. In fact, on some routine sampling occasions, a downstream sample was unable to be taken due to evapotranspiration of all the water entering the practice, proving this system to be effective at both removing nutrients as well as reducing overall water load downstream.

After the wastewater garden was sized to accommodate peak wastewater volumes, a trench was dug and lined with rubber sheeting, to ensure the wastewater would be contained long enough for treatment. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

The biochar amendment is created by placing a mixture of dry wood and dry plant material into a trench and lighting it on fire. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

Once the plant materials have burned down to charcoal, but before they turn to ash, the fire is extinguished. This material was used as a soil amendment. Biochar adsorbs chemicals, and provides a surface amenable to helpful denitrifying bacteria. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

How successful has it been?

A few months after planting, the vetiver grasses were taking root and the system was working well enough to prevent any effluent from being discharged during typical weekday conditions. The farthest grasses from the septic tank began to dry up as the effluent was effectively taken up by grasses nearer the influent water source.

This project demonstrates the applicability of green infrastructure and natural systems to provide additional treatment of wastewater. This and similar cost-effective solutions can be implemented in various scenarios to support other treatment strategies.

The trench was filled with layers of wood chips and biochar, which both offer treatment to wastewater. The wood chips were covered with layers of sand and soil and planted with vetiver grass. The grass seedlings are sterile, to eliminate the possibility of it becoming invasive. The grass can thrive in harsh conditions, and through its roots and evapotranspiration in its leaves is able to utilize nearly all of the hotel’s wastewater. Photo © Ridge to Reefs

Lessons learned

- The work is ongoing and maintaining progress requires thoughtful planning of development, wetlands and wastewater infrastructure. Successful watershed management requires local vigilance and advocacy, which has been strong in Guánica.

- Applying nature-based solutions effectively improves system function and efficiency and can achieve high levels of treatment at relatively low cost.

- Finding the perfect solution at the expense of doing nothing is ineffective; environmental damage is better prevented than repaired.

- Targeted analysis and pollution tracking lead to effective initiatives and improvements, such as the Guánica Bay Watershed Management Plan.

- Holistic consideration of watersheds is the most effective way to identify problems and create targeted nature-based solutions.

- Increasing local capacity by employing local collaborators and developing trust through partnerships was a major contributor to project success.

Funding summary

Hotel Nature-Based Wastewater Gardens ($60,000)

Coastal and freshwater pollution tracking efforts ($25,000)

5 acres of treatment wetlands including coordination, design and permitting and construction ($700,000)

Resources

Partners

Hotel Parador Guánica 1929

Local builder with a backhoe

Local engineer who supplied the vetiver grass

University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Horn Point Laboratory

Protectores de Cuencas (Treatment wetlands and pollution)

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation provided the project funding under their seagrass restoration/mitigation for past vessel groundings and oil spills program