Partnering to Manage Lionfish in the Bay Islands, Honduras

Location

Bay Islands, Honduras

The challenge

The Bay Islands of Honduras sit at the eastern edge of the Mesoamerican Reef, which is the second largest barrier reef in the world. Reef systems surround all the Bay Islands and smaller cays, ranging from barrier to fringing reefs. Since the 1950s, the economy of the Bay Islands has been tightly integrated into global markets, although the nature of that engagement has changed over time. In the 1950s-1960s, the lobster, conch, and shrimp industry were the mainstay, then in the 1970s, there was an influx of diving tourism. Beginning in the 1990s, and continuing to the present, large-scale cruise ship tourism became a driving economic force. As tourism increased, so did emigration from mainland Honduras to the Bay Islands. Today a diverse population inhabits the Bay Islands, but this influx of people has stressed the natural resources in the area.

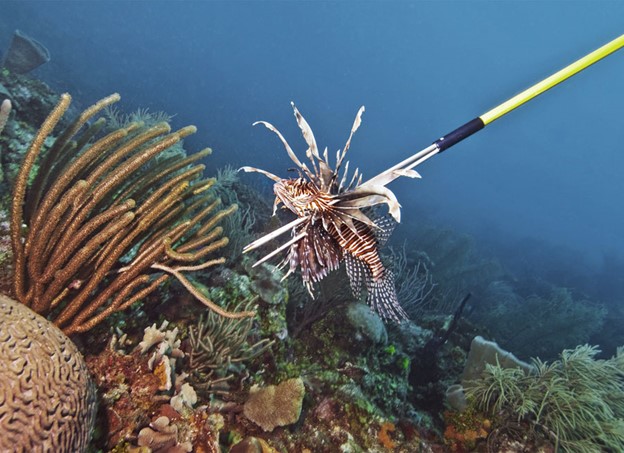

Lionfish have become a major threat to native fish populations throughout the Caribbean and have been documented in the Atlantic since the 1990s. It is theorized that the presence of lionfish is due to either accidental release from the aquarium trade or ballast water from the Pacific. When lionfish were first noticed in Belize in 2008, and soon spotted in the Bay Islands, managers had little time to plan a response. The lionfish began invading the shallow reefs and within two years they could be found throughout the entire region. In 2009, lionfish (Pterois spp.) were observed in the Bay Islands National Marine Park, a protected area spanning 6,471.5 km2, with several management categories ranging from no-take zones to multiple use areas.

Lionfish, an invasive species in the Caribbean. Photo © Antonio Busiello

Managers in the Bay Islands noticed declines in reef fish biomass across the Bay Islands – even in areas with fewer resident lionfish. One alarming discovery was the decrease in cleaner fish, like damselfish (Stegastes spp.). Cleaner fish feed on the dead skin and parasites of other fish. Cleaner fish are particularly vulnerable to lionfish, as they unknowingly approach the lionfish to remove dead skin and parasites, only to become prey. Researchers were also finding larvae of many other native fish in the stomachs of lionfish when they were dissected.

Actions taken

In Honduras, the national government provides limited (to no) funding to manage the reef systems of the Bay Islands, so local and international NGOs must seek grants to support reef management. With the increasing numbers of lionfish on the Bay Islands’ reefs, managers and local NGOs began strategizing ways to rid the area of these invasive species. They tried using nets, traps, and a “suction method” in which lionfish were siphoned out of the water with a PVC pipe. In addition to this, and, inspired by its success in the eastern Caribbean, managers began to target lionfish by spearfishing. They found spearfishing to be the most successful method to remove the fish.

The local Bay Islands NGOs worked together to successfully petition the Fisheries Department to allow permits for spearfishing lionfish. Both Roatán Marine Park and Bay Islands Conservation Association (Utila Chapter) helped to train divers, including staff from local dive shops and advanced divers, to find and spear lionfish on the protected reefs. The training helped to foster better relationships between different NGOs in the area. Local and international NGOs, including the Healthy Reefs Initiative and the Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL), began learning from one another and working together.

Funding for the training came from individual divers paying for training and a voluntary fee that dive centers agreed to add to their services. When the initiative started, licenses were only given to dive instructors and dive masters. Currently, the license and training process includes recreational divers that meet the organization’s requirements. For about $70, divers can purchase a license, a spear, and one hour of training. The voluntary fee revenue is put towards eradication of lionfish and supports many of the conservation projects Roatán Marine Park carries out.

Diver, Roatán. Photo © Antonio Busiello

Local skilled fishers (mainly from the Garifuna community) are also being trained to catch (without SCUBA), clean, cook, and market lionfish. Since lionfish are the most sustainable option to choose while dining, Roatán Marine Park and the Utila Chapter of the Bay Islands Conservation Association initiated the Lionfish Derby and Cook Off. This local event engages dive operators in a hunting competition and works with community cooks to prepare recipes with lionfish, which has helped promote adoption of lionfish as an option for restaurants. Lionfish can now be found on the menu of approximately 40 restaurants on Utila and Roatán, with filets being sold to mainland grocery stores and delis.

How successful has it been?

According to local divers and NGOs, spearfishing is decreasing the numbers of lionfish in popular dive sites in the Bay Islands. However, it is only effective if it is done in conjunction with properly managed areas. Though it is too early to determine the overall effect of the spearfishing initiative, ongoing assessments of the reefs reveal that there is an increase in biomass of native reef fish where lionfish are hunted. Nonetheless, further research on non-touristic areas and deep waters needs to be carried out to ensure spearfishing is reducing the number of lionfish and not just shifting them to new locations. Initial research from 2017 and 2019 discovered high numbers of large lionfish in mesophotic (low light) coral ecosystems.

At the beginning of the lionfish program, the potential abuse of the spearfishing permit was an ongoing challenge. Some local fishermen, who were trained and given licenses, illegally hunted protected reef fish such as snapper and grouper. This was observed when patrol boats found these fish speared in local fishers’ boats around the islands. However, as the lionfish program grew over time, community awareness and patrolling efforts have resulted in hunters more consistently abiding by the established regulations. Roatán Marine Park has also been aided other organizations, such as the Utila Chapter of the Bay Islands Conservation Association, in facilitating the purchase of equipment and supplies.

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Partnerships between local and international NGOs: The widespread lionfish invasion compelled many local NGOs to come together. These partnerships have enabled NGOs to pool their resources and expertise to better manage marine protected areas.

- A united front: The NGOs presenting a united front was important to improve the visibility of Bay Islands conservation issues at the national and international level. Where there used to be a few separately managed MPAs, there is now one large MPA – Bay Islands National Marine Park – which includes the three main islands and integrates the Cordelia Banks Site of Wildlife Importance and the Sandy Bay – West End Special Marine Protected Zone. The NGOs coordinate their messages and their initiatives, which has been critical to support the government in its efforts to control lionfish in the Bay Islands.

- The need for abridging organization: International NGOs, like CORAL and the Healthy Reefs Initiative, help to create neutral ground in a contentious local NGO environment. Reef health monitoring training also helped bring together local NGOs.

- Spearfishing is more successful when paired with concurrent management: Reefs that were found to be more resilient to the lionfish invasion were already adequately managed. For example, areas that had better water quality and higher levels of surveillance and enforcement had lower populations of lionfish and higher populations of grouper (Epinephelus sp. and Mycteroperca sp.). In areas with higher diversity, unlikely lionfish predators could emerge.

Funding summary

50% – 60% of the enforcement and other conservation projects carried out by the Roatán Marine Park are funded through voluntary donation fees from dive shops and an eco-store that is locally managed. There has been an increase in fundraising through grants since tourism decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lead organizations

Healthy Reefs Initiative

Coral Reef Alliance

Bay Islands Conservation Association Utila

Roatán Marine Park

The Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment Program

Partners

Government of Honduras

Resources

Roatán Marine Park Lionfish Program

Lionfish Guide to Control and Management

Written by: Ian Drysdale, Honduras Coordinator for the Healthy Reefs Initiative

Jenny Myton, Honduras Field Rep for the Coral Reef Alliance

Giacomo Palavicini, Executive Director of the Roatán Marine Park

This case study was adapted from: Cullman, G. (ed.) 2014. Resilience Sourcebook: Case studies of social-ecological resilience in island systems. Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.