Coral Nurture Program

Location

Great Barrier Reef, Australia

The challenge

Actions taken

Example of Coralclip® deployment. Photo © John Edmondson/Wavelength Reef Cruises

New Coralclip® attachment, securing branching Acropora. Photo © John Edmondson/Wavelength Reef Cruises

Operators tending to nurseries and outplanting using Coralclip®. Photo © David Suggett

Surveying outplant success as part of the “Phase two” kick-off workshop among multiple GBR tourism operators, staff, researchers and GBRMPA. Photo © John Edmondson/Wavelength Reef Cruises

How successful has it been?

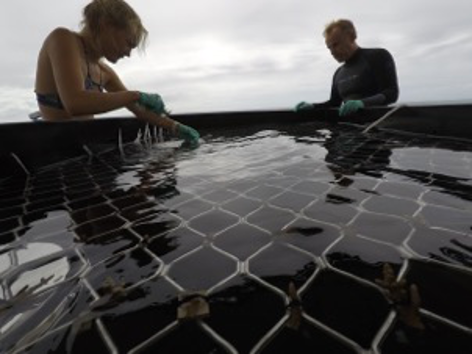

Application of the floating coral propagation nursery platforms, Opal Reef, GBR. Image shows growth of coral after 12-18 months propagation from fragments. Photo © David Suggett

“On-deck” seeding tray initially trialled to sow frames with fragments during the early phases of deployment. Photo © David Suggett

Shade deployed over the platforms during the 2020 GBR heat wave. Photo © John Edmondson/Wavelength Reef Cruises

Lessons learned and recommendations

Adapting nursery and outplanting design to fit location-specific requirements. Tools were conceived specific for the conditions that had driven the need for restoration. For example, numerous coral species (across all growth morphologies) had been impacted at GBR sites, and therefore floating platforms were designed in favor of existing “coral tree” structures to consistently accommodate any taxa, but also within often physically dynamic outer reef sites (Suggett et al. 2019).

Monitoring and implementation. Based on the extent of outplanting achieved in phase one for the test site, it was clear that attempting to ‘fate track’ 1,000s of outplants was impossible, and instead the outplant ‘success’ evaluations were established around ecological approaches using marked replicate plots of reef (and un-amended controls). Initial installation of nursery platforms at all sites provided very visible demonstrations relatively quickly to the operators and their tourist customer base of active site rehabilitation practices. Active outplanting was slower to adopt, and ultimately was best executed in targeted ‘campaigns’ when staff were available without impacting on regular operations.

Empowerment and capacity building is key. Empowerment and capacity building are at the core of the approach and philosophy of CNP. Stakeholders want to save the reef, and researchers want to help support robust methods to do this. Therefore, the partnership we built between researchers and tourism operators (or any other stakeholder) capitalized on the passion and drive of all involved to make positive change. The desire to optimize effective practice(s) tailored to the GBR has been critical in ensuring key lessons are learned prior to initiating projects purely for commercial gain, in particular where the ecological impacts are yet to be fully resolved. Importantly, scientific rigor has been central in driving increased social licensing, learning through implementation, but under well controlled environmental and social conditions. This has been central in building trust amongst researchers, stakeholders and the wider public to better define when restoration is (and isn’t) appropriate for the GBR.

Funding summary

Lead organizations

University of Technology Sydney

Wavelength Reef Charters

This case study was developed in collaboration with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) as part of the report Coral Reef Restoration as a Strategy to Improve Ecosystem Services: A Guide to Coral Restoration Methods.