Community Support for Watershed Management Leads to Ridges to Reefs Protection in Palau

Location

Palau, Micronesia

Rock Islands, Palau. Photo © Stephanie Wear/TNC

The challenge

Palau is located approximately 800 km east of the Philippines and consists of a series of islands approximately 459 km2 in total size. Palau’s coral reefs are considered one of the “Seven Underwater Wonders of the World.” Located on the northeastern margin of the Coral Triangle, Palau’s coral reefs have both high species diversity and high habitat diversity. Palau’s reefs contain more than 350 species of hard corals, 200 species of soft corals, 300 species of sponges, 1,300 species of reef fish, and endangered species such as dugongs, saltwater crocodiles, sea turtles, and giant clams. In addition to Palau’s diverse marine resources, it has the highest terrestrial biodiversity of all countries in Micronesia.

Coral bleaching during the 1998 bleaching event was as high as 90% at some sites, with average mortality reaching 30%. Following the bleaching event, the construction of a ring road around Babledaob Island (the largest Palauan Island) began. The road construction led to widespread clearing of forest and mangroves, causing soil erosion into rivers and coastal waterways that impacted seagrass beds and coral reefs. At the same time, Palauans started noticing declining coral reef health and fish stocks, along with degraded quality of freshwater resources. Studies conducted by the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC) revealed that the reef degradation was a direct result of land-based sediments, which resulted in reduced coral cover, lower coral recruitment, and excessive algae growth. Reefs in Airai Bay, a lagoon on the southeastern end of Babeldaob, were particularly affected by sediment.

Palau’s coral reefs have both high species and high habitat diversity. Assessing the biodiversity of the area was a step in the development of the Protected Area Network. Photo © Paul Marshall

Actions taken

Research on reefs that were impacted by bleaching and land-based sediments brought greater awareness of ecosystem connectivity, which shifted the conservation efforts in Palau to entire watershed areas. PICRC scientists presented their findings to communities in Babeldaob to demonstrate how terrestrial ecosystems protect coastal water quality and coral reef health. In response, community members lobbied the governing body of Airai state, the second-most populated state in Palau, to ban the clearing of mangroves that act as important buffers between the marine environment and terrestrial runoff.

In Palau, it has always been easy to garner interest in marine conservation because the fish provide a source of protein for Palauan families. In contrast, limited interest in conserving forests has resulted in a lag in terrestrial conservation. When the research showed the negative impacts of land clearing on the marine environment, including soil erosion and poor water quality, Palauans began to understand the need to protect forests and fresh water for water security. Traditional and elected leaders then came together to discuss how they could ensure water security for their communities. The creation of the Babeldaob Watershed Alliance (BWA) successfully merged the interests of communities, government agencies, conservation practitioners, and traditional leaders to protect entire watershed areas that ultimately protect the water source.

The creation of the Babeldaob Watershed Alliance was an effort of young conservation practitioners who saw the need to conserve terrestrial systems. These young champions enlisted the guidance of Paramount Chief Reklai of Melekeok, who then inspired Chief Ngirturong of Ngermelnegui state, and the adjacent state. The two traditional Chiefs and elected leaders of the two states established the largest terrestrial protected area that protects the water source for both states. After seeing the successes of this effort, other states began to join the Alliance and establish terrestrial protected areas within their states to protect water sources. Today, nine of the ten states in Babledaob are now a member of the Alliance.

How successful has it been?

Prior to the formation of the Babeldaob Watershed Alliance and its conservation efforts, there was only one terrestrial protected area: Lake Ngardok. Through BWA’s efforts to raise awareness and assist local communities to establish terrestrial protected areas, there are now seven additional watershed protected areas [Ngerderar (Aimeliik), Ngermeskang (Ngeremlengui), Diong er a Did (Ngardmau), Kerradel Conservation Network (Ngaraard), Orsoulkesol (Ngiwal), Ngardok (Melekeok), and Mesekelat (Ngchesar)], with a total coverage of 25.2 km2.

A major success of the BWA was the signing of “Master Cooperative Agreements” (MCA) between several states on Babeldaob that identify collective conservation goals and incentives for progress toward these goals. The BWA has also improved communication between local communities, government agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and conservation organizations including the Micronesia Conservation Trust. This has improved coordination and streamlined assistance to meet local priorities. All nine members who signed and became official members of the Master Cooperative Agreements established their respective state watershed protected areas. The only members without watershed protected areas are Ngarchelong and Ngatpang, which have private landowners within the watersheds; thus, they considered a state ordinance to regulate buffers. Since then, a 60-feet stream buffer and 300-feet radius around water supply catchment regulations has been mandated by the Palau Environmental Quality Protection Board, which was an active BWA technical team member.

The Babeldaob Watershed Alliance, with support from The Nature Conservancy and the Palau Conservation Society, was instrumental in engaging nine Babeldaob states and three outlying states in Conservation Action Planning. Conservation Action Planning helped each of the twelve sites identify important conservation targets, threats, and key strategies to address these threats. All twelve sites used the information to draft and finalize management plans. This has allowed them to access funding from the Green Fee through the Protected Area Office and Protected Area Network Fund. The Alliance (now titled the Belau Watershed Alliance) continues to assist these sites by working with partners to increase organizational and management capacity.

Additionally, the BWA updated their strategic action plan through the 2018 GEF Pacific Ridge to Reef International Waters.

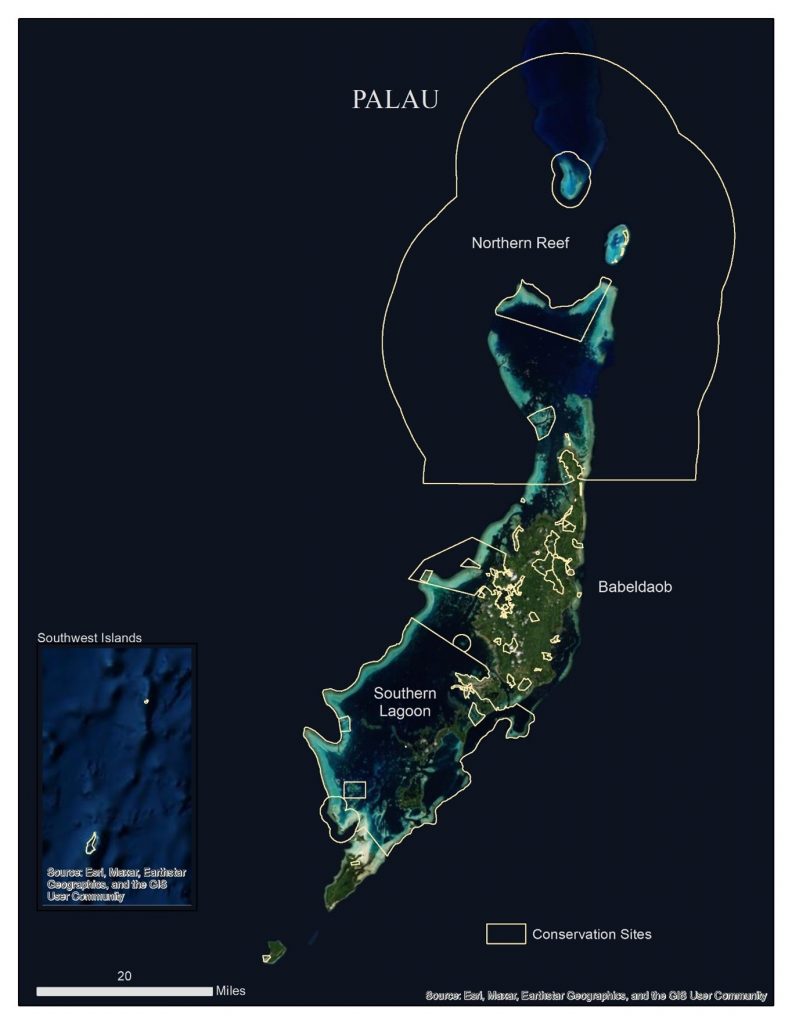

Map of Palau Protected Area Network and other designated conservation areas. Image © Michael Aulerio

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Relevance to livelihood—Conservation targets must be linked to quality of life. Shift the focus from species and ecosystem conservation towards protecting community culture and ways of life. The BWA found natural allies in the traditional chiefs who, despite the modern democratic government, are still widely recognized as stewards of all commonly shared resources and defenders of the Palauan culture and way of life.

- Leadership —Identifying an individual who can act as project champion is key. The charismatic leadership of High Chief Reklai added credibility and authority to the BWA’s message, and they engaged the traditional leaders of other states to rise to the same challenge.

- Relevant and sound science—Accessible and effective communication of sound scientific information is essential. The scientific data documenting the negative impacts of sediment on coral reef communities increased awareness in some and empowered many others by validating what they were already seeing on their reefs.

- Awareness of social, cultural and political context—Palau, much like other small cultures in a modernizing world, has complex, sometimes subtle, but often intersecting social, cultural, and political landscapes. Understanding and navigating through this complexity is not always emphasized enough in conservation projects. In the case of the BWA, young local conservation practitioners who understood the science and the culture were able to communicate the scientific information and leverage community support.

- Reducing/managing land-based source of stress to the marine environment will help build reef resilience through more rapid recovery following major natural disturbances.

- Healthy herbivore populations on the reefs will facilitate coral recovery through high recruitment and post-recruitment survival.

- BWA primarily benefitted the state policy makers. They regularly updated them on environmental issues and assisted in developing state policy to support sustainable development. BWA also assisted policy makers in science-based decision making. The Alliance created a forum for state policy makers and technical resource partners to work directly with each other to address development issues that states face. BWA is necessary, but there should either be a dedicated secretariat or a rotating responsibility among the state members that functions independently from the national government to encourage ownership of the BWA among states. Alternatively, it could be institutionalized within the state Speakers Association (with Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and the Environment support) to empower the state legislatures with regular engagement with technical experts to support policy-making and learning exchanges and to reinforce collaboration.

Funding summary

The Nature Conservancy

The Wallis Foundation

Government of the Republic of Palau (in kind)

Palau International Coral Reef Center (in kind)

German Lifeweb

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

US Fish and Wildlife Service

Lead organizations

Government of the Republic of Palau

Ministry of Resources and Development

Partners

The Nature Conservancy

Palau Automated Land and Resources Information System (PALARIS)

Other government offices: Bureau of Agriculture, Bureau of Marine Resources

Coral Reef Research Foundation

Palau International Coral Reef Center

Palau Conservation Society

Belau Watershed Alliance (BWA) (formerly the Babeldaob Watershed Alliance)

Resources

Biodiversity Planning for Palau’s Protected Areas Network, An Ecoregional Assessment

Impacts of Riparian Forest Removal on Palauan Streams

Trapping of Fine Sediment in a Semi-enclosed Bay, Palau, Micronesia