Fisheries Surveillance and Enforcement

Effective management of coral reef fisheries cannot succeed without an adequate legal framework, effective law enforcement, and compliance efforts. However, inquiries with environmental and fisheries authorities around the world reveal a reality that is common in every surveyed country: there are not sufficient vessels and personnel for enforcement, and when vessels, personnel, and equipment do exist, few vessels are operative due to the lack of funds for spare parts, fuel, or routine maintenance operations. Furthermore, when patrols are carried out and poachers apprehended, the individuals who violate the law are rarely fined due to outdated laws, corruption, or non-existent judicial follow-up.

Local patrol staff of the Kofiau Field Station encounters a non-local fisherman operating illegally within the Marine Protected Area. The fisherman's catch is noted, and he is instructed as to the regulations in the area. Kofiau, part of the Raja Ampat Islands of Indonesia, is located in the Coral Triangle, an area containing what may be the richest variety of marine species and corals in the world. The people of Indonesia's Raja Ampat islands rely on the sea as their most important source of food and income. Photo © Jeff Yonover

Fishery management strategies such as the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) or the closing of fishing areas or seasons often require the establishment of a framework where authorities, the private sector, local communities, NGOs, academic institutions, and other stakeholders agree to collective action. Establishing such a framework and enforcing respect for the law are the cornerstones of a good governance program.

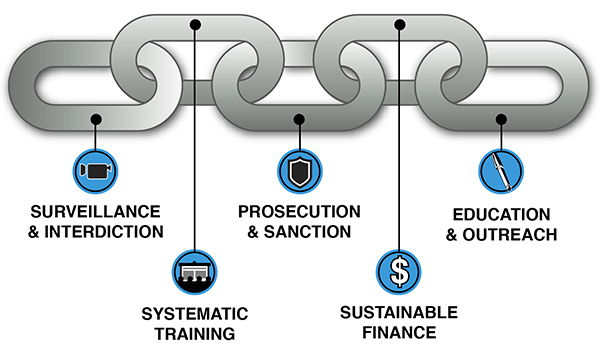

An effective law enforcement system should dissuade potential lawbreakers from committing illegal activities, since it will ensure that the consequences/risks associated with apprehension outweigh economic gain. There are 5 key components in the development and implementation of an effective surveillance and enforcement system:

- Surveillance and Interception. One must first identify the most cost-effective suite of sensors for detection in a given area, and then use the information supplied by these to respond and intercept the illegal activity. The response depends on institutional or community capacity i.e. available vessels and staff, fuel, protocols, etc.

- Systematic Training. The regulations, systems, and tools are only as useful as those who are trained to operate and maintain them.

- Prosecution and Sanction. It is not worth investing millions of dollars in surveillance systems if there are no repercussions. Administrative or criminal prosecution and sanctions are necessary to ensure compliance.

- Sustainable Finance. Enforcement systems cost money. Funding for establishment and long-term operations must be identified and secured.

- Education and Outreach. It is critical to foster community buy-in as well as to inform stakeholders of rules, regulations, and sanctions.

To learn more about each part of the enforcement chain, click the blue circles below:

Surveillance and Interdiction

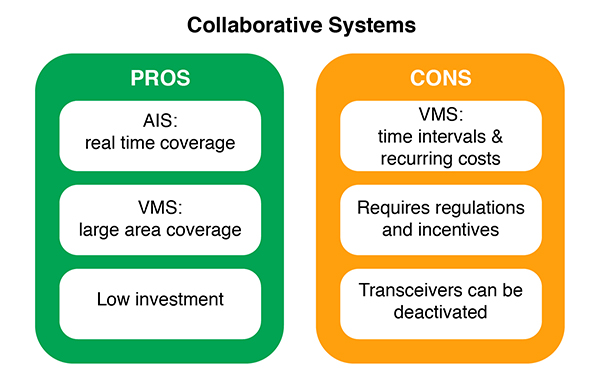

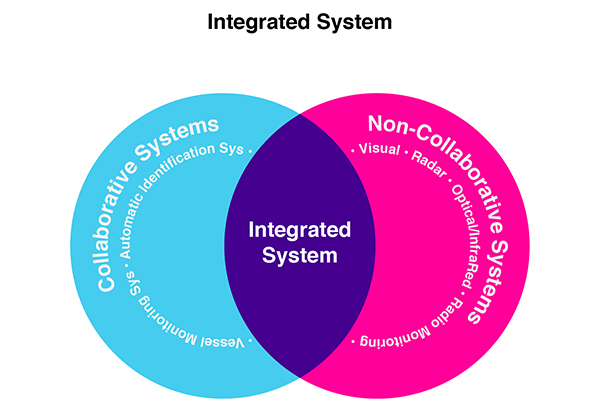

A surveillance system should include the most cost-effective suite of sensors for detection that provides information for appropriate response and for successful interdiction in a given area. Typically there are two types of systems that are used for surveillance: collaborative and non-collaborative.

Collaborative Surveillance Systems require active location transceivers on-board vessels. There must be a law that mandates the use of transceivers and dictates penalties for deactivation. Fishers must be part of the process for the implementation of this type of system. There are two main types of collaborative technologies:

An Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) is an on-board vessel identification system that operates over marine VHF (Very High Frequency) and transmits vessel information like ship name, course, speed, and precise location in coastal and inland waters. AIS usually works in continuous mode and the system coverage range is similar to other VHF applications. The information is sent to shore base stations or vessel traffic service centers to monitor the movement of vessels. Read more about AIS.

A Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) is also an on-board vessel system that uses satellites to collect and transmit data on vessel name, location, course, etc. Read more about VMS.

Pros and Cons of Collaborative Systems. Source: WildAid

- AIS provide real time monitoring of small and fast vessels.

- VMS provide location information over large areas and open ocean. VMS transmit an encrypted message (not open to the public, but directly to authorities).

- The capital and operating costs of both AIS and VMS are relatively low (costs can range from $50,000 for local confined system to $5M+ for a national system of about 8,000+ vessels) and both systems are being deployed in the developing world.

- VMS provide location information every 1–6 hours, which is not appropriate for artisanal vessels. In addition, a transceiver costs $800–$1,300 and there is a monthly cost associated with the service ($20–$60, depending on signal frequency).

- AIS also require the purchase of a transceiver. There are no recurring costs for the fisher when shore-based AIS stations exist; however, with the advent of AIS migration to satellites, recurring costs could also become a factor.

- Collaborative systems require a law to mandate their use and to provide incentives for adoption. For example, in Ecuador the use of transceivers conditions access to fuel subsidies.

- Transceivers can be deactivated and require stiff penalties for violations. In Mexico, there is a law that requires the installation of VMS transceivers on commercial fishing vessels, but the law does not specify penalties for transceiver deactivation. This loophole allows fishers to deactivate their transceivers if they do not want to be detected.

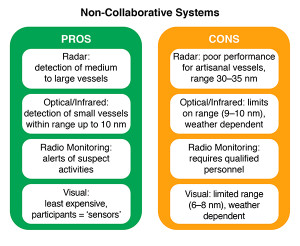

Non-Collaborative Systems do not require transceivers or the participation of stakeholders in the process. These surveillance systems detect vessels in a specific geographic area. There are several types of non-collaborative surveillance systems, such as visual, radar, optical (images taken from satellite, manned or unmanned aerial vehicles), and/or infrared cameras. These sensors are either located at strategic sites on the coastline and/or mounted upon mobile platforms, such as patrol vessels or drones. The monitoring of radio communication is another non-collaborative option for identifying suspicious activity.

Pros and Cons of Non-Collaborative Systems. Source: WildAid/TNC

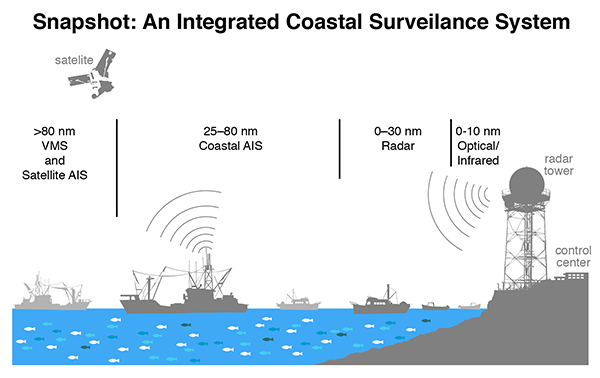

- Radars are ideal for the detection of medium to large vessels up to 30 nautical miles (nm).

- Optical, video, and infrared cameras are ideal for the detection of vessels up to 10 nm.

- Beyond that range, they can be mounted on drones for an additional 20–30 nm of coverage.

- Radio monitoring can be a cost-effective way to detect suspicious activities.

- Visual observation by officers and stakeholders is limited to 8 nm and appropriate for community-based enforcement systems. They are the least expensive and are effective for nearshore contexts.

- Radars do not perform well beyond 6 nautical miles from the coast in the detection of small wooden or fiberglass vessels.

- Optical, video, and infrared cameras are limited to 10 nm.

- Infrared cameras are expensive.

- Drones are quite expensive, increasing in cost as their autonomy range increases beyond 5 nm.

- Radar monitoring requires dedicated and trained personnel.

- Visual observation by officers and stakeholders is typically limited to 8 nm.

Integrated Surveillance Systems Approach

No one sensor can provide full coverage, so surveillance systems are often designed using a variety of sensors in an integrated system. To determine the necessary technology for designing a surveillance system, it is critical to consider detection distance, target size, and types of materials used for vessels (wood, fiberglass, or aluminum). For example, radars or high power cameras can be used in combination with VMS transceivers and AIS. The radars or cameras can be placed near productive fishing grounds to detect vessels that have deactivated their VMS transceivers and are fishing in a prohibited area. See the figure below for details on types of collaborative and non-collaborative surveillance technologies and their respective coverage ranges.

A Snapshot of an Integrated Surveillance System. Source: WildAid/TNC

Back to Enforcement Chain (top)

Systematic Training

A comprehensive training program on the topics in the table below is required to strengthen the professional capacity of management and enforcement teams.

| Subject | Description |

|---|---|

| Surveillance, Interdiction and Boarding | • Operational planning and preparation • Use of visual and electronic sensors for patrols • Boarding protocols: inspections, required documents, what to check and look for, documenting the inspection. Training should include prosecutors. • Interrogating and confronting suspicious crews • Crime scene protocols. Collecting and handling of evidence • Operational report. Items and information that should go into a report |

| International Maritime Organization (IMO) Basic Training | • First aid • Survival at sea • Fire fighting |

| Operational Planning and Administration of Control Center | • Control center functions, including risk assessment, use of assets, reports, communication protocols, surveillance and documentation protocols • Telecommunication lines and collaborative procedures with coastguards • Situational assessment and real-time reports • Reading and using nautical charts • Reading and using land maps • Search and rescue • Providing first-aid services in the field • Considerations for personal security during patrols and boarding |

| Basic and Advanced Courses on Outboard Motor Maintenance | • A basic outboard motor maintenance course provided by the manufacturer • One or two rangers should be assigned to attend the advanced course on outboard motor maintenance and critical repair. |

Standard Operating Procedures that Reinforce Training

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) will ensure that enforcement efforts are implemented effectively, that they guide daily tasks and institutionalize and maintain professional standards. SOPs, in combination with good reporting and feedback strategies, help new personnel learn appropriate actions, responses, and methods more quickly. To maximize their efficiency, SOPs should be updated regularly in accordance with the input and experience of officers. At a minimum, SOPs should be developed for the following subjects:

- Directing and ensuring communications between officers, vessels, and managers, as well as with other agencies.

- Coordinating active operations. The center also implements interceptions (or interdictions) and sends backup as needed.

- Maintenance of all archives including user manuals and SOPs. Communication with external agencies and managing confidential information.

- Maintenance of technology and resource inspections.Knowing that the personnel profile fits the functional needs of the different posts.

- Pre-departure checks: verify that all the bridge gauges and indicators are operating, test the speed control and guidance system, prepare underway logs, personal equipment, navigation equipment - radar, GPS, echo sounder, charts, DF, check ship's logbook open and duly noted for the commencement of the patrol, and raise international fisheries pennant to show that you are on a fisheries patrol.

- Checks of other equipment: obtain machine report and verify that portable radios are functioning; check that boarding equipment such as life jackets, binoculars, rifle, hand guns, flares, boarding flags, net gauge, or other fishing regulation measuring equipment is on board.

- Submission of a pre-departure report to the operational director or supervisor.

- Establishment of patrol strategies, such as multiple boat patrol, patrol with a cross-search leader, barrier patrol, radar patrol, and patrol with searchlights.

- Determine if patrols will be performed undercover.

- Determine the distance and speed of vessels to be intercepted and detained.

- Delineate minimum training requirements for personnel in the inspection of different types of vessels and their associated risks.

- Establish protocols for the chain of command, control, and abnormal situation assessment (ex: the escalation of a detected crime).

- Establish communications protocols to keep constant communication with the control center (ex: perform periodic checks every 15 minutes).

- Set restrictions on the use of cell phones or personal cameras while performing a boarding inspection (these can put the security/success of the operation at risk). Allow only the team leader to use them.

Back to Enforcement Chain (top)

Prosecution and Sanction

Enforcement systems require effective criminal, civil, and/or administrative sanctions and punitive actions. Prosecution is different in every country, but the sanctioning process for environmental violations is typically very slow. Effective compliance systems are important in order to avoid delays and lost trials, which ultimately cause economic losses for the state in terms of wasted patrol resources and loss of natural capital. While the legal framework is unique in each country, the following types of sanctions should be considered in the development of enforcement systems:

Criminal/Civil Sanctions. The following actions are recommended in order to improve judicial proceedings:

- Establish a standardized boarding report format with recommendations from the relevant legal authority’s office.

- Train officers to fill in reports according to this format.

- Formalize official relations between officers patrolling the area and their provincial and/or federal counterparts.

- Carry out training workshops for judges, attorneys, and lawyers once a year on marine and fisheries-related rules and regulations.

- Assign additional lawyers from NGOs or support agencies to follow up on environmental marine violations or crimes.

- Set up private prosecutions for major cases using external lawyers.

Administrative Sanctions. In order to expedite the sanctioning process, where possible administrative sanctions should be carried out at the local level. The severity of measures should correspond to the seriousness of the violation. Non-economic sanctions should also be considered, for example:

- Vessel detention for a limited time;

- Restriction of sailing authorization permits;

- Seizure of fishing gear;

- Temporary suspension of permits for ships, crew members, or ship-owners;

- Revocation of operating licenses for ships, ship-owners, agents, maritime personnel, or fishers.

Back to Enforcement Chain (top)

Sustainable Finance

Effective enforcement systems require funding. However, most marine resource enforcement efforts receive limited central government support, leaving administrators with very little resources to enforce laws. User fees and increased cost-effectiveness of operations are two common strategies to sustain enforcement efforts.

User Fees The governments of Ecuador and Palau have initiated protected area taxes to directly support conservation efforts. The green tax in Palau, for example, raises over $5M annually, while the Galapagos entrance fee raises approximately $1M for enforcement in the marine reserve. These revenue-generating schemes are politically feasible, appeal to tourists who want to help protect natural and cultural resources, and can provide critical funding for enforcement. Unfortunately, the legal frameworks in many countries do not permit the creation and administration of user fees. As a result, some resource management agencies and MPAs have developed co-management agreements with NGOs, tourism operators, or communities to increase funds and capacity for enforcement efforts. For example, the NGO WildAid manages external donations from the tourism industry for the Galapagos National Park Service to fund critical spare parts and patrol vessel maintenance.

Decreasing Cost of Operations Enforcement programs should also look to increase the cost-effectiveness of operations. In programs evaluated by WildAid, typically 70% of maritime enforcement costs are comprised of personnel salaries and fuel. At least two strategies can support cost-effective enforcement operations that reduce fixed costs while ensuring that the area to be monitored can still be covered:

1) Performance-Driven Acquisitions. It is important to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the fishers/area users, violators, the geographic area, and institutional capacity when designing an enforcement system. Appropriate staffing, surveillance equipment, number and type of fishing vessels, and outboard motor size are some of the critical variables to consider in the design of an enforcement system.

What not to do: Many sites make the mistake of having a donor or a sales representative prescribe the technology or the enforcement system design, which often results in a system that is overly sophisticated and costly for the specific area. There are many examples of donated vessels that end up costing more to maintain in the long run than they are worth to enforcement efforts.

2) Use-Appropriate Technology. Enforcement strategies that combine technology with patrols are most cost-effective. As most sites possess a limited maritime staff, systems can be designed that combine the use of surveillance sensors with the strategic placement of buoys for the mooring of patrol vessels that remain in close radio communication with the control center officer and respond only when a potential violation occurs. Although this strategy does not eliminate the need for some patrols, it does reduce the amount of fuel used, as the vessels can sit idle at moorings for extended periods of time.

What not to do: Carry out constant patrols that cost staff time, fuel, and wear and tear on vehicles and vessels.

Back to Enforcement Chain (top)

Education and Outreach

A fisheries officer from the National Fisheries Department of Papua New Guinea teaches a fish handling class to residents of Potou village on the coast of Lolobau Island in Kimbe Bay, West New Britain province. Potou village is participating in the plan for locally managed marine areas (LMMA), part of the extensive network of marine protected areas created in Kimbe Bay. Photo @ Mark Godfrey

In many places where successful enforcement occurs, community buy-in and well-informed stakeholders play a key role. Education and outreach is critical to fostering the communities' knowledge of and compliance with rules and regulations and can also lead to community-based enforcement. Once regulations are in effect, agency enforcement teams should develop a simple education and outreach plan directed towards local fishers, foreign fishers, tourism operators, and the local community. Activities to consider include:

- Development and distribution of a simple fact sheet outlining zoning, regulations, restrictions, and fines or sanctions;

- Engagement of enforcement officers in outreach activities;

- Listing regulations at key ports and fishing cooperatives;

- Radio and television spots;

- Outreach to local primary and secondary schools with exhibits, videos, and informal discussions;

- Community events;

- Information at municipal offices;

- Pamphlets provided at airports and tourism kiosks;

- Merchandise (T-shirts and bracelets).

World Cup Ecuadorian Soccer Player, Ulises de la Cruz, Showing Support for Shark Campaign. Photo © WildAid

Effective communication with a variety of stakeholders is essential for any successful enforcement effort. To learn more about methods for planning and implementing stakeholder communications click here.

The information in this section was provided by WildAid. For more information please contact WildAid.

Resources

Coral Reef Fisheries Resource Library

Near Shore Artisanal Fisheries Enforcement Guide

Turneffe Atoll Marine Reserve: Control and Vigilance System Design

Palau Northern Reef Assessment: Control and Vigilance System Design

Patrolling the Galapagos Marine Reserve

Recent Trends in Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Systems for Capture Fisheries

Galapagos National Park Prevents Overfishing in Game of Cat and Mouse

Fishing for Solutions: A Fisheries Management Guidebook for Non-Fisheries Managers