Coral Propagation and Restoration in Florida

Location

Florida’s Coral Reef

The challenge

Since the 1970s, reef-building corals have experienced a significant and catastrophic decline throughout Florida and the Caribbean due to a number of causes, including disease, coral bleaching, hurricanes, and localized anthropogenic impacts. Seven species of coral found in Florida have been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act; Acropora cervicornis and Acropora palmata in 2006 and Dendrogyra cylindrus, Orbicella franksi, Orbicella faveolata, Orbicella annularis, and Mycetophyllia ferox in 2014. Since that listing, Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease has impacted the entirety of Florida’s Coral Reef, affecting about half of the coral species on the reef, and caused a further decline in live coral cover. Additionally, very little evidence of natural recovery through recruitment of juvenile corals has been observed.

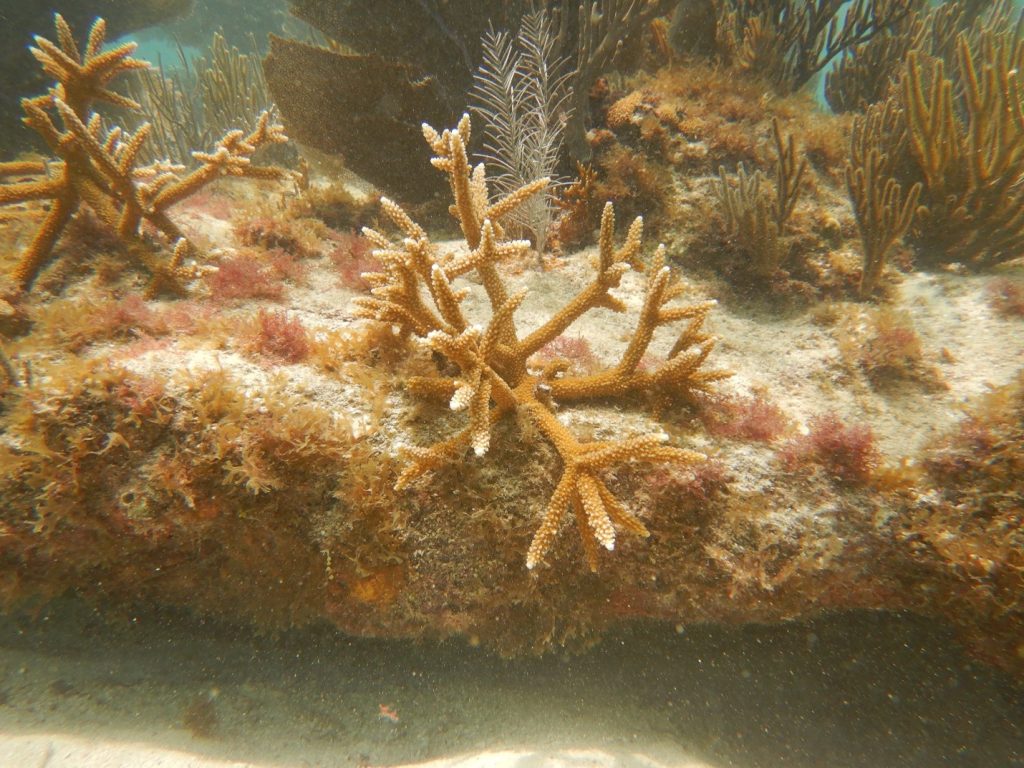

Nursery-raised staghorn coral one month after outplanting to a reef in Dry Tortugas National Park. Photo © Caitlin Lustic/TNC

Actions Taken

History

In 2000, Ken Nedimyer of Sea Life, Inc. (and founder of the Coral Restoration Foundation and Reef Renewal) and his daughter began to propagate A. cervicornis coral fragments as part of a 4-H Youth Development project for her high school. Nedimyer later approached The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary about using the fragments for coral restoration purposes. In 2004, TNC and Nedimyer received funding through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)-TNC Community-based Habitat Restoration Grant Program to initiate a pilot study. This pilot project was successful and in 2006 led to an expansion project, funded through the same source. New nurseries were built throughout Florida by Nova Southeastern University, University of Miami, and Mote Marine Laboratory. In 2009, when American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) monies became available, the groundwork had already been laid to significantly increase the scope of this project and funding in the amount of $3.3 million was secured to further expand the nurseries over a three-year timeframe. The project expanded to include a nursery in the Middle Keys managed by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and in St. Croix and St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI).

Montastrea cavernosa corals grow on a coral tree in Mote Marine Laboratory’s offshore nursery. Photo © Caitlin Lustic/TNC

Coral Nurseries

With growth rates faster than any other Caribbean coral species and asexual fragmentation as the dominant form of reproduction, Acropora corals can be efficiently propagated using low-tech in-water nurseries and thus served as a good species to learn about nursery propagation. Strategically located where natural and human threats are low, in-water nurseries can provide a stable setting for small, vulnerable coral fragments to grow and thrive when properly maintained by local coral farmers. When coupled with advanced genetics, nursery-reared corals with high survivorship potential can be outplanted to adjacent degraded reefs to enhance the genetic diversity and size of remnant coral populations.

Over time, it became apparent that the Acroporids were not the only species that needed to be restored, and partners in Florida expanded their nurseries to work with some of the other reef-building species – Montastrea cavernosa, Orbicella spp., Pseudodiploria spp., and others – and continue to experiment with new species in the nursery setting. Simultaneously, corals that were collected ahead of the Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease margin as part of a statewide effort to save important genetic material are now housed in labs, zoos, and aquaria across the US and some are being used to experiment with breeding in species that have not yet been bred in captivity. The number of corals and the breadth of species is expected to increase significantly over the next few years as more is understood about raising and propagating these rescued corals.

How successful has it been?

Over the years, the number of outplants per year has increased from a few thousand to tens of thousands. Due to the success of this work, a Caribbean Acropora Restoration Guide: Best Practices for Propagation and Population Enhancement was produced for other similar projects in the Caribbean region. A global update is in the works and expected to be published in late 2022.

Additionally, new initiatives are underway to be more strategic about where, when and which species are being used for restoration. In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), and a suite of restoration partners launched Mission: Iconic Reefs, a plan to restore seven reefs within FKNMS waters to historic coral cover. The plan considers not just the placement of corals, but also aims to restore ecosystem balance where it has been lost by manipulating sites prior to restoration, introducing keystone herbivores to help control macroalgae growth, and performing maintenance activities after restoration to increase the chance of long-term success of the outplants. In addition to that plan, TNC is currently working with reef managers in Florida to develop a statewide coral reef restoration strategy that will identify priority areas for restoration to help guide funding allocation and increase the likelihood that restoration efforts are contributing to the overall recovery of Florida’s Coral Reef. Following that strategy, a more detailed plan will be developed for the Kristin Jacobs Coral Reef Ecosystem Conservation Area, the portion of reef that runs along South Florida from the St. Lucie Inlet to Biscayne National Park.

Lessons learned and recommendations

Planning for restoration, particularly in areas with complex goals and more than one species involved, should occur before a nursery is installed. Guidance for planning for restoration activities can be found in A Manager’s Guide to Coral Reef Restoration Planning and Design. Overgrown nurseries can lead to disease or just general poor health, particularly during summer months when corals are already stressed from increased water temperatures, so planning should include considering how many corals are needed and when they will be outplanted.

Funding summary

Current partners receive targeted funding from a variety of sources. Initial funding for the project was provided by:

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

NOAA Community-based Restoration

Restore Act through Monroe County

NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program

Lead organizations

Partners

The Nature Conservancy

Coral Restoration Foundation

National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council

Mote Marine Laboratory

University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science

Nova Southeastern University

Biscayne National Park

Dry Tortugas National Park

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Southeast Florida Coral Reef Initiative

NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program

Resources

Caribbean Acropora Restoration Guide

Restoring Seven Iconic Reefs: A Scientific and Collaborative Plan

A Manager’s Guide to Coral Reef Restoration Planning and Design