A Bleaching Response Plan Leads to Increased Protection of Tobago’s Reefs

Location

Republic of Trinidad and Tobago

The challenge

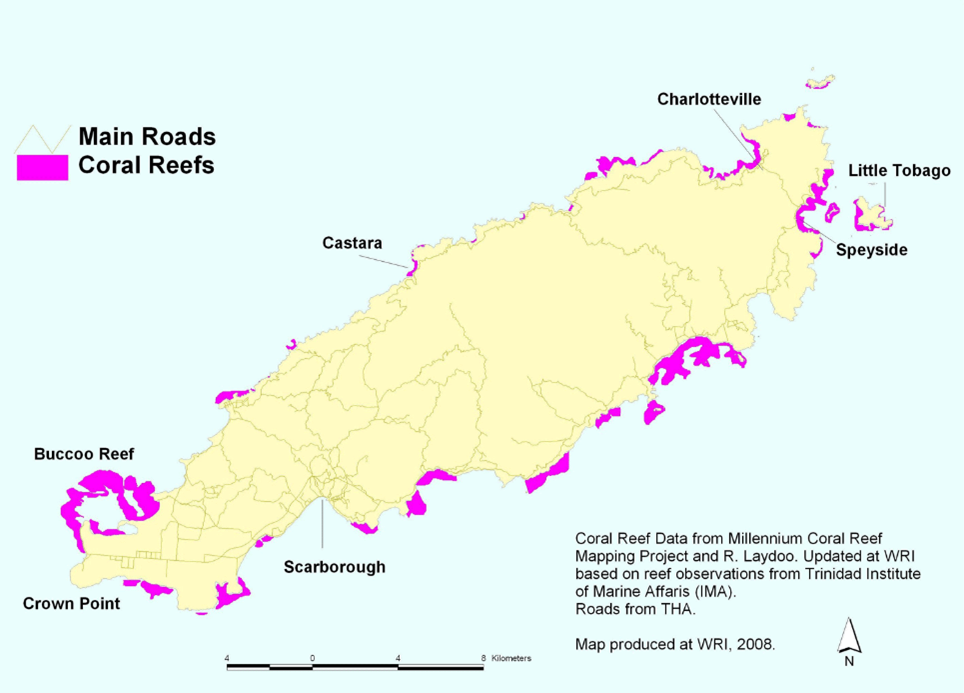

Tobago represents the south-eastern limit for coral reef growth in the Caribbean. Two areas in Tobago are renowned for their coral reefs. The first is Buccoo, located in the southwest of the island within the Buccoo Reef Marine Protected Area, whose barrier reefs protects surrounding communities and fishing harbors from wave and surge from annual storms. The second is located to the northeast of the island off the village of Speyside and is home to one of the largest brain corals in the world (over 5 m/16 ft wide and 3 m/10 ft high).

Brain coral in Buccoo Reef. Photo © Maritime Ocean Collection

The reefs at Buccoo and Speyside together with other smaller reefs fringe the rest of the coast and are highly valued for the food and coastal protection benefits they provide. The reefs also provide livelihood opportunities from tourism, which may contribute up to 50% of the island’s GDP. ref These reefs are also biogeographically unique, in that they have developed under sub-optimal conditions of high turbidity and nutrients, resulting in reefs with high sediment tolerance compared to other clear water reefs typically found throughout the region.

Map of coral reefs of Tobago.

The foremost threat to these coral reefs is ocean warming. Successive mass coral bleaching events have increased coral mortality, reduced the number of reproductive corals and slowed reef growth, exacerbating reef specific local scale threats such as excess inputs of land-based sediments and nutrients, unsustainable fishing practices, unsustainable tourism, and the spread of the lionfish (Pterois spp.). Further, despite the presence of a legal framework to protect coral reefs, the absence of clear management mandates and siloed approaches to management continue to hamper the sustainability and resilience of these reefs.

Actions taken

Recognizing the ecological and socioeconomic importance of coral reefs to the island, in the face of several local and global threats, Buccoo Reef (and associated mangroves, seagrasses, and lagoon) was designated a no-take protected area in 1973, which today represents the only marine protected area on the island. In the intermittent years several attempts have been made to increase the boundaries of the Buccoo Reef Marine Protected Area, increase its protections under the provisions of the Environmental Management Act, and create new protected areas, but to limited success.

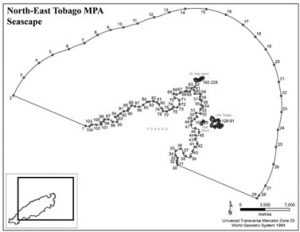

Most recently, through a technical cooperation with the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (GORTT) initiated policy reforms aimed at preventing biodiversity loss and improving the management of protected areas (PAs), including the establishment of a marine protected area network.

Proposed pilot Northeast Tobago marine protected area.

Ongoing actions include coral reef monitoring, scientific research, environmental capacity building within communities and education and outreach. The cornerstone of coral reef monitoring and research has been led by the state-run Institute of Marine Affairs (IMA) who has been investigating the reefs of Tobago since the 1980s. While initially developed to understand the natural history of the Buccoo Reef Marine Protected Area, the program now extends to all coastal ecosystems around the island, with focus on health, environmental impact, restoration, fisheries, and coastal zone management.

In contrast, the non-governmental sector has been at the forefront of community engagement and community-based management. Organizations such as the Buccoo Reef Trust (BRT), Education Research in Charlotteville (ERIC) and The Speyside EcoRangers (SEMPR) have built successful programs and advanced coral reef conservation by bridging the science-management divide through community based and stakeholder focused advocacy, outreach, education and training programs.

How successful has it been?

In 2010, a mass coral bleaching event occurred on Tobago reefs, but unlike previous events the local managers were ready. An informal Bleaching Response Plan (subsequently formalized) resulted in the coordinated efforts of park managers, fisheries officers, marine scientist, and dive operators to assess the impact of the bleaching and communicate the implications to the public. The plan was developed collaboratively with support from local (IMA, BRT, Department of Marine Resources and Fisheries, Association of Tobago Diver Operators, Department of Environments and Division of Tourism) and international partners (The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA)). The plan aims to coordinate strategies among agencies for monitoring and communication of coral bleaching impact and response. The plan consists of an early warning system (EWS), bleaching assessment and monitoring, and a communication plan. The network of state, NGO, private sector (e.g., dive tour operators, boat tour operators, and hoteliers) and recreationalists is critical to the success of the EWS. The network acts as a first source of information for disturbances (e.g., coral bleaching, algal blooms, and invasive species) observed on the reef. Two Integrated Coral Observing Network (ICON) Coral Reef Early Warning Systems (CREWS), which measure near real time SST and other ancillary oceanographic and meteorological data, are enhancing and expanding the potential of the Bleaching Response Plan by providing readily available, publicly accessible data.

This was the first time such an approach was used in regard to coral bleaching in Trinidad and Tobago. The implementation of the Bleaching Response Plan resulted in the identification of several potential nodes of resilience, as well as the identification of resilient species (three major sites are discussed in Alemu and Clement 2014 ref). This information has, to an extent, been mainstreamed into the decision support system for reef management in the selection of future project sites and MPA locations. However, various limitations continue to slow the pace of reef conservation on the island.

Coral gardens, Tobago. Photo © Maritime Ocean Collection

Lessons learned and recommendations

- For the sustainability of projects like these where stakeholder participation is key, more effort should be invested in the conversation with stakeholders before project/program development rather than after, to ensure that their needs are being met, rather than trying to mesh a project’s needs with stakeholder desires.

- Inequities in power and trust between stakeholders can limit the advancement of collaborative management programs but establishing ground rules that balance power might help, when mediation is not possible.

- Not all stakeholders have the same feelings about reef conservation – the response plan should be flexible enough to incorporate the needs of the stakeholders.

- Resilience can be a unifying word where different stakeholders may experience coral bleaching differently, and each stakeholder may have difference incentives for being part of this partnership; therefore, it is paramount that all stakeholders have one shared goal.

- Identifying pro-active, government champions that have some autonomy and authority is key to pushing the agenda of resilience programs.

- Using data already collected by state agencies makes it easier to incorporate the response plan into an existing workplan, project or budget line.

- Prioritizing data dissemination especially to NGOs can help maintain relationships and provide support to monitoring agencies that are unable to share bleaching related information to the public in a timely manner.

Funding summary

The Nature Conservancy

The Institute of Marine Affairs, Trinidad and Tobago

Department of Marine Resources and Fisheries, Tobago House of Assembly

Lead organizations

Institute of Marine Affairs, Trinidad and Tobago

Department of Marine Resources and Fisheries, Tobago House of Assembly

Association of Tobago Dive Operators

Partners

The Nature Conservancy

Tobago Department of Marine Resources and Fisheries