Disturbance Response Monitoring of Florida’s Coral Reef

Location

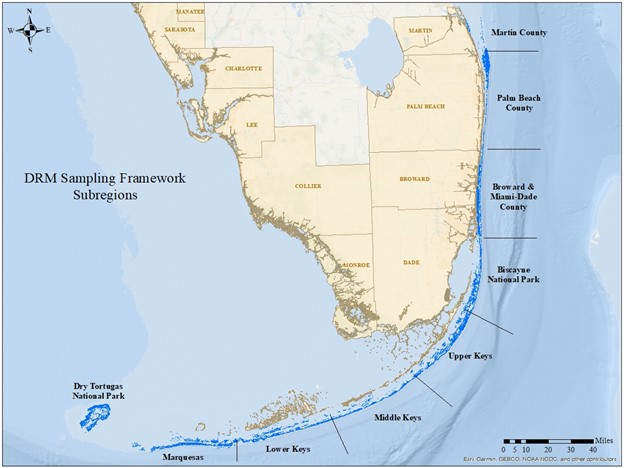

Florida Keys and southeast Florida mainland, USA

The challenge

The Florida Reef Resilience Program (FRRP) was established as a collaborative network of coral reef resource managers, researchers, and other stakeholders to develop strategies to improve the health of Florida’s reefs and to enhance the sustainability of reef-dependent commercial and recreational enterprises. Because of the threats posed by climate change (e.g., rising sea surface temperatures and rising sea levels) the FRRP, led by The Nature Conservancy and supported by the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program, created the Disturbance Response Monitoring (DRM) program to annually assess reef condition during the months of peak thermal stress. Coral bleaching events in Florida date back to 1985; however, the first mass bleaching events were documented in 1997 and 1998 in association with El Niño. Another mass bleaching along the Florida Reef Tract (FRT) occurred in 2005 followed by the worst back-to-back coral bleaching events in 2014 and 2015 (Manzello 2015). With anticipated increases in ocean temperatures and frequency of coral bleaching events expected to rise due to climate change, coral mortality associated with thermal stress is of paramount concern. Since 2005, the DRM program and its partners have conducted annual surveys to document the extent and severity of coral bleaching and disease on the FRT.

The survey region spans from Martin County, Florida at the northern extent of the reef tract to the Dry Tortugas.

In addition to thermal stress, Florida’s coral reefs are currently experiencing a catastrophic, multi-year disease event known as stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) that has resulted in massive die-offs for >20 coral species (Aeby et al. 2019, Mueller et al. 2020). The disease is both virulent, causing acute tissue loss on highly susceptible species, and long-lasting by chronically affecting less-susceptible coral species for months to years after the initial pass of the disease (Aeby et al. 2019, Walton et al. 2018). First observed near Virginia Key in late 2014 (Precht et al. 2016), the disease has since spread throughout Florida’s reefs.

Despite ongoing research, the causative pathogen of SCTLD has not yet been identified. Intervention attempts to either slow or terminate the spread of SCTLD across Florida’s Coral Reef have not been successful although in some instances treating the lesions has helped arrest disease progression on individual coral colonies (Voss 2019, Neely 2020).

Additionally, large-scale coral restoration efforts are being planned by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FL DEP), NOAA’s Protected Resources, and the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission in the aftermath of SCTLD. A large majority of the corals that will be propagated for restoration are being preserved as part of a multi-partner coral rescue and gene banking effort to conserve the genetic diversity of Florida corals. Demographic assessments that identify where surviving corals persist in the endemic zone (no longer in the epidemic stage of SCTLD) will provide information on where to collect reproductive material for future restoration efforts as well as help to identify possible causes of resistance. Read a case study on SCTLD.

Actions taken

Although historically focused on bleaching, the DRM program has been very responsive in modifying its experimental design to account for the ever-changing nature of the stressors impacting the reef. This includes adapting its protocols in response to SCTLD. Besides providing geospatial information for tracking the leading edge of SCTLD, it added a Roving Diver Survey in 2018 and 2019 to estimate SCTLD prevalence across the reef. These objectives were tied to assisting other SCTLD response efforts and providing timely information for coral intervention and rescue efforts. Now that nearly 90% of the reef tract is endemic (prior exposure to SCTLD but no longer epidemic) the focus has changed to assessing the surviving population of corals that were most susceptible to SCTLD and identifying resilient reef areas that can support restoration and recovery.

Measuring corals along a transect in Palm Beach County. Photo © Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Between 2005 and 2018, the DRM program was managed by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Florida and funded by the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. In 2018, the oversight and management of the DRM program was transferred to the Florida Fish & Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI) of the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) because the DRM program was well aligned with the core mission of FWC and FWRI’s programmatic capabilities of managing large-scale monitoring and research projects (e.g., EPA-funded Coral Reef Evaluation & Monitoring Project).

How successful has it been?

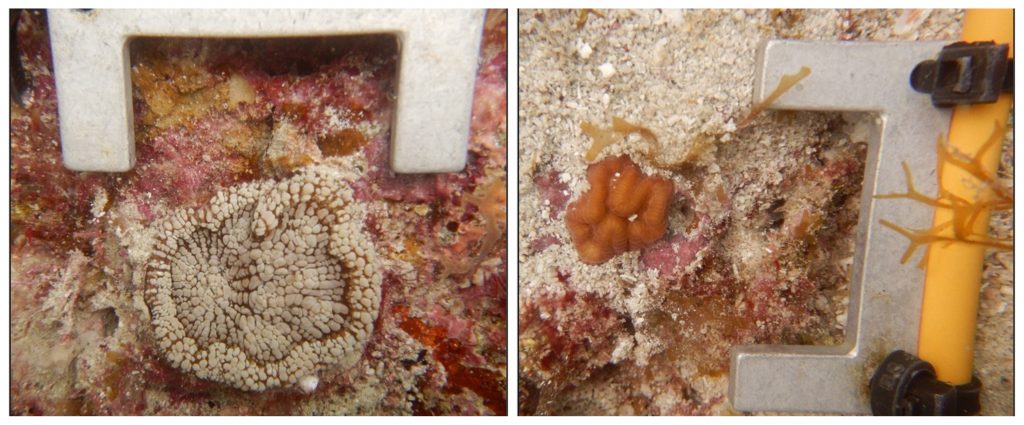

Over the last several years, DRM coral health and condition data has provided important information to determine the extent of SCTLD and coral bleaching and its potential impacts on the reef system. Numerous publications and technical reports have utilized DRM data to draw important conclusions on the impacts of coral bleaching and other disturbances on the reef community and long-term trajectories of coral survival (van Woesik et al. 2020, Muller et al. 2020, Lirman et al. 2014, and Lirman et al. 2011). With the inclusion of juvenile coral abundance in the 2020, 2021, and 2022 DRM seasons, this data will provide insight into whether there is new recruitment of susceptible species in the endemic zone (areas where SCTLD was previously present), which would indicate that natural recovery is happening.

Juvenile corals tallied along a transect in the Dry Tortugas. Left image is a juvenile coral of the subfamily Mussinae. Right image is a coral of the subfamily Faviinae. Photo © Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission

The DRM program also offers the opportunity for partners from across the jurisdictions of the Florida Reef Tract to work together under a unified effort. Collaboration across agencies, universities, and organizations allows for multiple sources of input and expertise towards the program and generates transparency across managers and researchers. This broader collaboration is becoming more important as the threats to Florida’s Coral Reef continually grow.

An integral feature of the DRM program is the web-based online portal allowing surveyors to enter DRM survey data remotely. The data entry system was developed by FWRI staff to be user friendly and validate all fields to reduce user error and improve quality control for a rapid turn-around of survey results. Once the surveys are complete and quality assurance has been performed, the DRM data is made available to the public through the online data report generator on the DRM website. The data report generator is accompanied by a link to a detailed metadata file which includes citation information and acknowledgments to funding sources.

From the data, an annual summary report is developed that provides bleaching and disease prevalence information across the reef zones surveyed. This Quick Look Report includes maps and summary tables as well as an overview of how the current year compares with past years results. All reports are accessible on the DRM website. Since 2005, over 3,500 surveys have been completed by 14 teams from federal, state, and local government agencies, non-profit organizations, and universities during the summer months. In recent years, the DRM has surveyed over 300 sites annually across the reef tract making the program the most intensive coral monitoring program in Florida.

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Success of this program is highly dependent on the collaboration and contributions of many different agencies and institutions. The scale of the survey is so great that it would not happen without collaboration. This has also resulted in a continued high level of commitment from the organizations involved.

- Identifying supplemental funding to allow different organizations that have staff and expertise, but lack funds, is critical. This has enabled a broad spectrum of institutional stakeholders to contribute.

- In the first year, the team was able to demonstrate that an undertaking of this scale was possible and that there was a broad institutional commitment. The success of this pilot effort helped attract additional partners who had initially questioned the feasibility of conducting such large-scale surveys.

- It is important to develop and maintain a simple protocol so that surveys can be completed rapidly during the period of peak bleaching occurrence; so that minimal but sufficient training is required; and so that the resulting data set is consistent.

- It is important to continue surveys each year regardless of the level of coral bleaching to keep surveyors up to date with the methodology in case of unexpected disturbances (e.g., 2014 and 2015 bleaching events). This also keeps the survey work in team members’ annual workplans and budgets, facilitating their ongoing participation.

- Coordination with other related monitoring programs is key. When the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program was developed, FRRP worked closely with them to try to align the two protocols to be complementary. Over the years, this has proven very successful for the following reasons:

- The arduous process of selecting sites is conducted jointly every other year, and the sites are then split between the two programs to avoid duplication of effort and complete more sites.

- The survey methods are similar enough that divers trained in one protocol can easily learn the other; this provides a larger pool of divers to both monitoring programs and allows for the sharing of time and resources.

- At least portions of the data sets can be used interchangeably in analyses, providing a more robust data set for tracking changes in the condition of the reef over time.

Funding summary

Environmental Protection Agency – South Florida Initiative

Florida Department of Environmental Protection – Office of Resilience and Coastal Protection

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Coral Reef Conservation Program

Florida’s Wildlife Legacy Initiative – State Wildlife Grant

Lead organizations

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Resources

Disturbance Response Monitoring (DRM) program

Disturbance Response Monitoring “DRM”