Five Characteristics of Effective MPAs

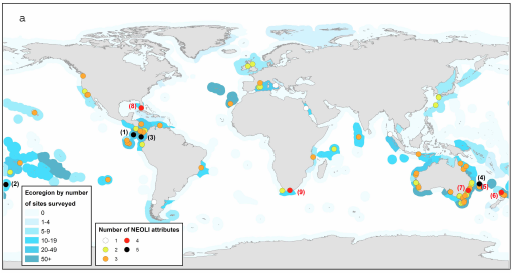

Dr. Graham Edgar and his 24 co-authors recently stirred up the marine conservation world with their article, “Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas five key features”. In this article, they review 87 MPAs at 964 sites (in 40 countries) around the world using data generated by the authors and trained recreational divers.

Their overall conclusion is that global conservation targets for the Convention on Biological Diversity that are solely based on the area of MPAs do not optimize protection of biodiversity. They found that effective MPAs (measured by biodiversity, large fish biomass, and shark biomass) needed to have 4 or 5 of the following characteristics: no-take, well enforced, >10 years old, >100 km2 in size, and be isolated by deep water or sand. Unfortunately, only 9 of the 87 MPAs had 4 or 5 of those characteristics, most of the remainder of MPAs were ecologically indistinguishable from non MPAs. The authors hope that reserves that are serious about biodiversity outcomes will adopt the 5 characteristics (when possible) and quickly see a rapid increase in the potential of a site to have regionally high biomass and species numbers. You can find the paper here, and see a conversation with some of the authors.

We asked Dr. Edgar some questions and here is what he said:

What can a manager of a smaller, newer, or not isolated MPA take from this paper, as they might not be able to influence those factors?

Concentrate on good enforcement, ideally through good will from the local community, and also through improved policing if required. Newer MPAs will age, so with good enforcement and some no-take zones, biodiversity goals are achievable in most locations. This is not assured, however, so ecological monitoring is needed to understand what is working and what can be improved, rather than assuming all is fine under the sea.

In regards to working with trained, skilled, recreational divers to collect data for this study: what would you recommend to coral reef managers who work with (or want to work with) recreational divers for their monitoring programs? What aspects of this part of the data collection led to success?

We found group participation helped during surveys, which were more enjoyable when motivated and like-minded divers could interact with each other. Also, one-on-one training and support to Reef Life Survey (RLS) volunteer divers is fundamental to consistent data gathering. Our divers can see that their efforts contribute directly to improved marine conservation management. Virtually all of the active divers from the start of the RLS program six years ago remain enthusiastic and continue to participate, a very positive statistic.

What surprised you the most in doing this study?

In terms of biology: the near absence of sharks and other large predatory fishes sighted by divers other than in MPAs, even off isolated unpopulated islands. By comparison with reports from cruising yachts and divers in the same areas only a decade or two ago, it seems clear that population numbers of big fishes and lobsters have declined precipitously in recent years.

In terms of governance: the fact that the developing world and the Southern Hemisphere are leading efforts to establish MPA networks. European and continental Asian countries have very few effective MPAs, despite huge ecological stresses and marine biodiversity assets that are remarkable and unique, but deteriorating.

What part of this research has made you feel the most optimistic for the future of MPAs?

The recent establishment of large no-take MPAs in isolated regions is a very positive step. Of course this is only one component of a global MPA system – we certainly need effective MPAs of a variety of sizes to encompass all ecosystem types worldwide – but it is great to see some refuges established that will assist the survival of large wide-ranging species, at least in the tropics.