Invasive Species

On coral reefs, marine invasive species include some algae, invertebrates, soft corals, and fishes. Invasive species are species that are not native to a region. However, not all non-native species are invasive. Species become invasive if they cause ecological and/or economic harm by colonizing and becoming dominant in an ecosystem, due to the loss of natural controls on their populations (e.g., predators).

Pathways of introduction of marine invasive species include:

- Ship traffic, such as ballast water and hull fouling

- Aquaculture operations (shellfish aquaculture is responsible for the spread of marine invasive species through global transport of oyster shells or other shellfish for consumption)

- Fishing gear and SCUBA gear (through transport when moving from place to place)

- Accidental discharge from aquaria through pipes or intentional release

Lionfish caught by a spear fisher, Pedro Bank, Jamaica. Photo © Tim Calver

Management Strategies

There are four main approaches in managing invasive species:

- Prevention – which requires an in-depth understanding of how invasive species are transported and introduced

- Detection – which requires timely and systematic ecosystem monitoring

- Control – which may be required to stop further spread and manage established populations

- Restoration – which may be required to assist the recovery of a degraded reef ecosystem

The local community removing invasive algae to restore near shore reef habitat in Hawai‘i. Photo © Mālama Maunalua

There are over 300 species of Sargassum algae, ref a group of marine brown algae. However, there are generally two types of Sargassum (floating and non-floating) that vary in their impact to reefs and management strategies needed to address them.

Non-floating Sargassum species are a threat to coral reef ecosystems when they become overabundant on a degraded reef, inhibiting the settlement and growth of coral recruits and reducing the capacity of a reef to recover after disturbances. ref

In the Atlantic, two species of floating sargassum, S. natans and S. fluitans, are responsible for causing large mats of algae blooms which are particularly harmful and prevalent on the Caribbean and West African coastlines. ref This invasion of floating algae in coral reef areas, causing reduced sunlight required by corals and anoxic and hypoxic conditions on reefs, as well as poor conditions on beaches that are detrimental to the tourism industry. ref

Close up on Sargassum fleshy macro-algae strands. Photo © Jeff Yonover

Management strategies include the active removal of Sargassum algae either by hand or using a suction device. However, the efficacy and long-term effects of these methods are largely unknown. ref Current recommendations include: ref

- Coupling removal with effective protection and potential reintroduction of herbivores

- Removing the holdfast (root) of the Sargassum algae

- Conducting removal in the early growing season of the Sargassum

- Incorporating the effect of seasonality and climate change in the Sargassum removal plan

Unomia

Unomia stolonifera, (formerly Xenia sp.) is a fast-growing soft coral that originates from the Indo-Pacific region and is now reported as invasive in the Caribbean. ref It is believed to have been introduced from the aquarium trade in Venezuela in the early 2000s. Due to its fast growth, high fecundity, and absence of predators, it is rapidly proliferating and overgrowing coral reefs and seagrass beds. Areas most heavily impacted in Venezuela now have up to 80% of the benthic cover dominated by Unomia, therefore eradicating a diverse array of native species. ref

There are no current management strategies for managing the spread of Unomia on coral reefs.

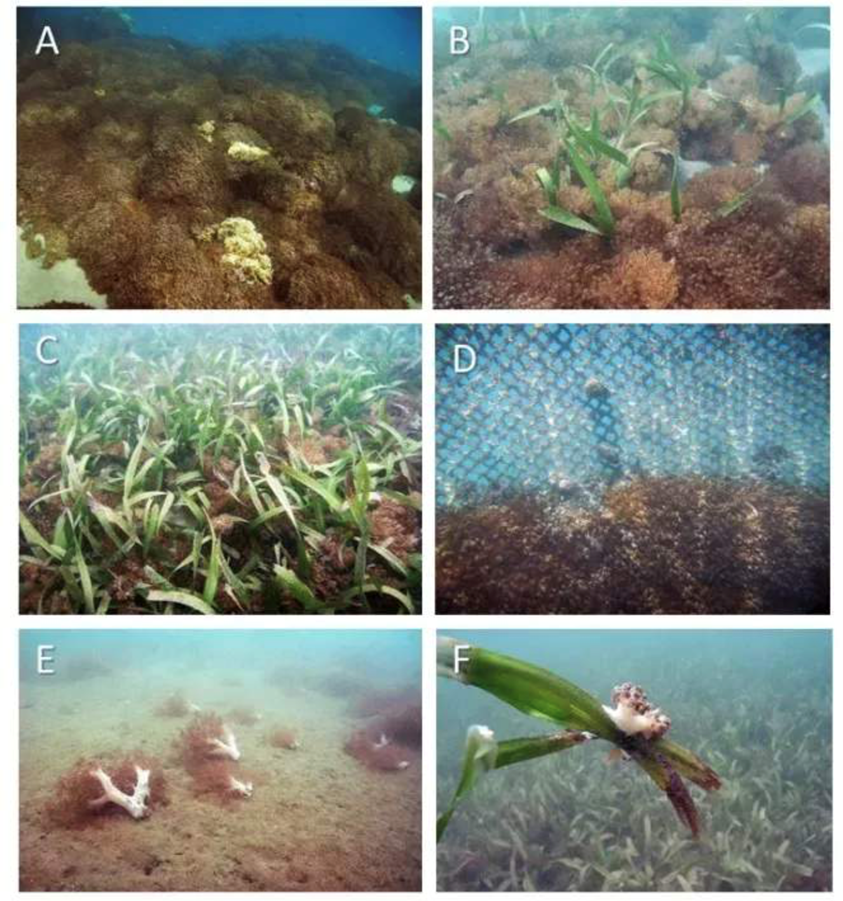

Underwater images of the invasive Unomia stolonifera in the study sites along the northeastern coast of Venezuela, Southeastern Caribbean Sea. (A) Colonies monopolizing hard reef substrate. (B) Colonies overgrowing the seagrass Thalassia testudinum. (C) Seagrass bed occupied by invasive octocoral. (D) Fishing net with colonies. (E) Drifted colonies on the bottom. (F) Detached T. testudinum with colonies floating with currents. Photo © Juan Pablo Ruiz-Allais

Lionfish

Native to tropical waters in the Pacific, lionfish are believed to have been introduced to the Atlantic waters along the Florida coast in the mid-1990s and have since rapidly expanded in range throughout the Caribbean. There are few native Atlantic and Caribbean species that could act as significant potential predators of lionfish. ref In the Caribbean and Atlantic, natural lionfish predators like groupers are overfished and therefore unlikely to reduce lionfish populations and their associated ecological impacts.

Lionfish control programs are in place throughout the Caribbean. In the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, special lionfish removal permits are now issued for collection of lionfish from Sanctuary Preservation Areas (SPAs), which are otherwise no-fishing, no-take zones. In other parts of the Caribbean, such as the Cayman Islands, programs have focused on encouraging local fishers to catch lionfish and encourage a market for lionfish through education campaigns, including brochures explaining how to safely handle and prepare lionfish.

Resources

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance: Prevention and Clean-up of Sargassum in the Dutch Caribbean

UNEP webinar on the science of Sargassum

Invasive Alien Species: A Toolkit of Best Prevention and Management Practices

State of Hawai‘i Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan

Marine Biofouling and Invasive Species: Guidelines for Prevention and Management