Bleaching Biology

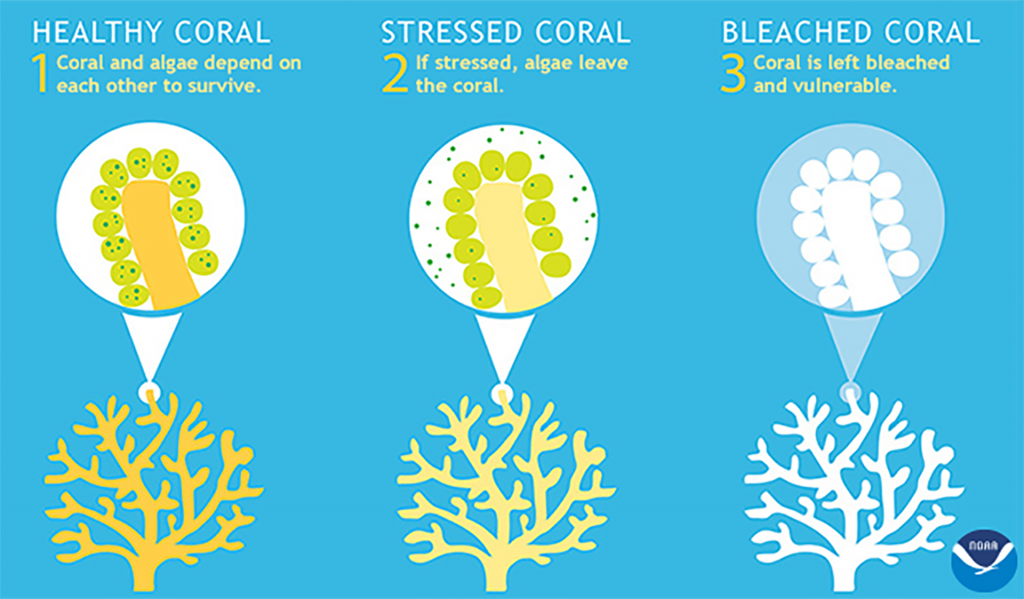

Elevated seawater temperatures in combination with strong sunlight cause thermal stress in corals. This stress can cause disruption of normal photosynthetic processes in the coral’s zooxanthellae which leads to coral bleaching.

Role of Temperature and Light

The main trigger of large-scale bleaching events is an increase in water temperatures above the normal summer maximum. At elevated temperatures, the photosynthetic system of zooxanthellae is easily overwhelmed by incoming light leading to production of reactive oxygen species. These are a source of oxidative stress in the coral’s tissue, causing the coral to expel zooxanthellae to avoid further tissue damage. While increased temperatures are the trigger for bleaching, light is also an important factor. Increased solar irradiance (i.e., the amount of light that penetrates the water column) can exacerbate bleaching risk, while corals that are partially shaded can tolerate higher temperatures before bleaching.

Recovery from Bleaching

Without the zooxanthellae to support their metabolic processes, corals begin to starve. Should water temperatures return to normal conditions soon enough, corals can survive a bleaching event. Where bleaching is not too severe, the zooxanthellae can repopulate from the small numbers remaining in the coral’s tissue, returning the coral to normal color over a period of weeks to months. Some corals, like many branching corals, cannot survive for more than 10 days without zooxanthellae. Others, such as some massive corals, are capable heterotrophs and can survive for weeks or even months in a bleached state by feeding on plankton. Even corals that survive are likely to experience reduced growth rates, decreased reproductive capacity, and increased susceptibility to diseases.

If a coral reef is exposed to stressful conditions that are known to cause bleaching, its fate is influenced by three key ecological attributes:

- Extent to which corals can withstand elevated stress without bleaching (resistance)

- Ability of corals to survive bleaching (tolerance)

- Ability of coral communities to be replenished (recovery) should significant coral mortality occur

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Variations in Bleaching Susceptibility

Corals vary in their susceptibility to bleaching. Consistent patterns of susceptibility can be seen among coral species, with a general trend of higher susceptibility in more intricate, branching forms and lower susceptibility in massive species, especially those with fleshy polyps. Corals can also acquire a greater tolerance to bleaching stresses if they are constantly exposed to higher temperatures or greater irradiance. Corals on reef flats, for example, will often be able to tolerate much higher water temperatures than colonies of the same species inhabiting reef slopes.

The type of zooxanthellae can also influence bleaching susceptibility. There are at least nine groups (called clades) of zooxanthellae currently recognized, and there may be many species within these groups. Zooxanthellae clades vary in their ability to tolerate elevated temperatures, and some corals have heat-resistant clades, and are therefore, more resistant to bleaching. However, corals with heat-resistant clades tend to grow more slowly, creating evolutionary trade-offs in the symbiotic relationship that maintains a diversity of clade-coral relationships.