Changes in Storm Patterns

Projections of Changes in Storm Patterns

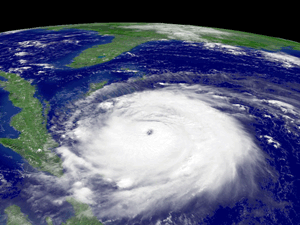

Hurricane Frances approaches Florida in September, 2004. Image courtesy NASA and NOAA.

Scientists have a difficult time determining whether climate change (particularly warming) has led to changes in tropical storm patterns. This is due to the large natural variability in the frequency and intensity of tropical storms (e.g., due to the El Niño Southern Oscillation), which complicate the detection of long-term trends and their attribution to increasing greenhouse gases. Other factors include limitations in the availability and quality of global historical records of tropical storms, inconsistency in data observation methods, the localized nature of the events, and the limited areas where studies have been conducted.

Since the mid 1970’s, global estimates of the potential destructiveness of hurricanes show an upward trend strongly correlated with increasing tropical sea-surface temperature. ref The number of strong hurricanes (Category 4 and 5) increased by about 75% since 1970, with the largest increases observed in the Indian, North and Southwest Pacific Oceans. The frequency of hurricanes in the North Atlantic has also been above normal over the last decade. However, improvements in our ability to observe cyclones may have biased these estimates. ref

Despite these challenges, many future projections based on high-resolution models suggest that anthropogenic warming may cause tropical storms globally to be more intense on average (with intensity increases of 2–11% by 2100). While some studies consistently project decreases in the globally averaged frequency of tropical cyclones, substantial increases are projected in the frequency of the most intense cyclones. ref

Impacts on Coral Reef Ecosystems

If tropical storms increase in intensity, then coral reefs will need longer times for recovery from impacts between storm events. Direct physical impacts from storms include erosion and/or removal of the reef framework, dislodgement of massive corals, coral breakage, and coral scarring by debris. Increasing storm impacts are also likely to cause fragile branching species (responsible for most structural complexity on reefs) to decline more rapidly than the proportion of massive corals, resulting in low structural complexity on impacted reefs. ref

In addition, stronger storms may also lead to greater coral damage due to increased flooding events, associated terrestrial runoff of freshwater and dissolved nutrients from coastal watersheds, and changes in sediment transport (leading to smothering of corals). When the intensity of storms becomes more frequent, coral skeletons are likely to become more susceptible to breakage under ocean acidification and therefore more susceptible to storm damage. ref

Storm damage on coral reefs is extremely patchy ref due to the substantial differences between storms in terms of their intensities, size, and movement. Damage can vary from removal of entire coral outcrops (over 10s to 100s of meters) in the direct path of a storm, to individual colony damage in more sheltered areas. ref Damage may also be driven by disturbance history, level of coral cover, type of coral community, and environmental factors such as exposure and circulation. ref

Recovery is also highly variable and depends upon interactions of numerous factors, e.g., scale of the disturbance, availability of larvae from surviving corals, availability of substrate for coral settlement, and the type of coral community that existed at the time of the disturbance.ref Changes in storm patterns also threaten associated coral reef habitats such as mangroves. For instance, large storm impacts have resulted in massive mangrove mortality in the Caribbean. ref