Detection of a Coral Disease Outbreak in Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi and Lessons for the Future

Location

Hanalei, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi

The challenge

Hanalei, on the North Shore of Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi, is a small community of about 450 permanent residents. The Hanalei region is rich in biodiversity and cultural tradition and is home to many species of high conservation value. Five ahupuaʻa, the traditional Hawaiian land division, drain into Hanalei Bay. There are also three culturally important fishponds, a traditional Hawaiian aquaculture technique that encloses or diverts stream waters into an enclosed near shore area for purposes of rearing fish for local consumption. The Hanalei River is one of fourteen American heritage Rivers in the United States.

Hanalei River and Valley. Photo © Hanalei Watershed Hui

Tourism is the main economic driver on Kauaʻi. Many community members operate small-scale tourism businesses. On the North Shore, only about 25% of the residents are long-term, permanent residents; many residential properties have been converted to vacation rentals, with many of these visitors and seasonal residents originating from the mainland United States.

The community is highly engaged in natural resource management and planning and has identified major causes of land-based pollution including the conversion of single-family homes to more intense commercial uses, inefficient wastewater management systems, natural erosion, over-use of fertilizers, and erosion and disturbance caused by feral pigs. Strong wave action characterizes the ocean waters surrounding Hanalei, ensuring that the water surrounding Hanalei’s reefs are generally well mixed and water residence times are low.

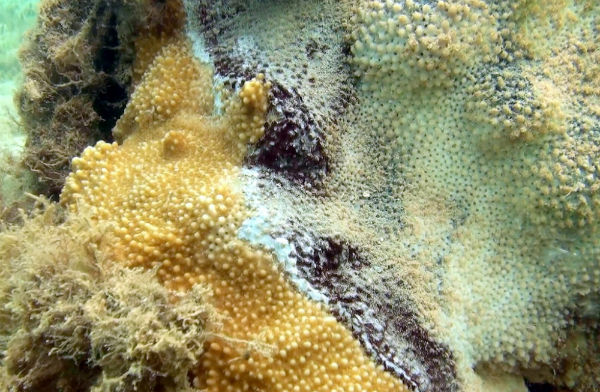

In 2004, scientists studying the reefs on the North Shore of Kauaʻi first observed a black band coral disease at low levels. Then, in 2012, outbreak levels of the disease were reported to the volunteer reporting network, Eyes of the Reef (EOR). Scientists with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), University of Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (UH), and the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have now confirmed that the disease affects three species of rice corals (Montipora capitata, M. patula, and M. flabellata), and, with some variation across sites, approximately 1-8% of colonies of these species. While these percentages are relatively low, Montipora corals are the dominant reef-building corals on North Shore reefs and therefore the disease has the potential to have a significant impact on reef structure and function. Black band coral disease can move through a coral colony very fast. Typically, a disease front of cyanobacteria can be observed. It leaves behind dead coral tissue and algae covers the exposed skeleton.

Black band disease persists on these coral species and has been consistently observed on corals during the summer months since at least 2018. The disease appears to be seasonal, with cases decreasing in the winter months when the waters are cooler. The Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources is currently analyzing data to determine if there is a trend of declining coral cover as a result of the black band disease affecting corals every summer.

Answering media questions about the coral disease response. Photo © Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources

Actions taken

Once the Eyes of the Reef Network confirmed the coral disease outbreak, USGS, UH, and NOAA conducted an initial assessment, according to the established protocol of the Rapid Response Contingency Plan (RRCP). The RRCP provides the Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) and its partners with a plan to respond to events affecting reef health, including coral disease, coral bleaching, and crown-of-thorn starfish (COTS) outbreaks. The first step after receiving the report was getting partner scientists and government biologists to confirm and assess the extent of the disease. In 2012, a UH microbiology laboratory identified a cyanobacteria responsible for the disease, similar to diseases that have been observed in the Caribbean and the Indo-Pacific. A UH doctoral student surveyed Kauaʻi’s reefs in 2013 and confirmed that the disease was predominantly affecting the North Shore (86% of the 21 northern surveyed sites had the disease present, while only one site out of four in the south had the disease). The press covered the disease outbreak extensively, which brought attention and community concern about the issue.

Documenting the impact of the black band disease. Photo © Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources

There is relatively little known about coral diseases and less about how to manage diseased reefs; therefore, research is a major part of the first phase response. Since the disease was first observed, DAR partners studied topics including disease transmission, potential treatments, the influence of coral health on coral susceptibility to the black band coral disease, how environmental factors correlate to the incidences of black band disease, and an experimental treatment option. The DAR Response Team published a report in 2015 examining the prevalence and distribution of the black band coral disease outbreak on Kauaʻi’s north and south shores to identify any correlations with environmental stressors. The report recommends continuation of the EOR community reporting program to act as an early warning and detection system for future disease outbreaks, increased monitoring of at-risk reefs during elevated SSTs, and continued collaboration between multiple agencies, among other recommendations. See the Resources section for additional research.

Lesions from black band disease on a coral (healthy coral is to the left of the disease front, dead coral is to the right). Photo © University of Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology

Members of the coral disease laboratory at University of Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology have been piloting an experimental treatment for affected coral colonies. Application of marine epoxy putty to edges of the disease lesions on affected corals has been found to effectively stop or slow disease progression on corals. While application of marine epoxy is effective, it is not feasible to administer this treatment to every coral colony with the disease, but it may be a good preventative management protocol for reefs that have very low disease prevalence or on areas with recent outbreaks that could be contained through the application of epoxy.

How successful has it been?

The Management Response Team—formed by DAR in 2014 with partners that conducted the initial disease assessment, as well as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), DAR biologists and education specialists, and a coral specialist from the Kewalo Marine Laboratory—reviews incoming data regarding the disease outbreak, communicates the event to the public, and evaluates management options. Thus far, the team has prioritized projects that will identify environmental drivers for the disease, evaluated potential management strategies, and launched a website to post information about the response. The black band disease outbreak is ongoing and no recovery has been reported; when the black band kills coral, the exposed skeleton often becomes covered in turf algae which inhibits coral recovery.

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Monitoring and research should be prioritized over eradication. Observations and research thus far have concluded that eradication of the black band disease is not feasible. Therefore, efforts should be focused on monitoring the disease’s presence around Kauaʻi and continuing to research trends and factors that may contribute to increased presence of the disease.

- Reducing land-based pollution is critical. One study researching the physicochemical drivers of the black band disease suggests that high nutrient levels, likely associated with pollution from upstream cesspools (of which there are many in Kauaʻi), are stressors that make the coral more prone to disease. Converting cesspools to sewer systems would be one approach to mitigating these stressors. Other sources of land-based pollution such as fertilizer and stormwater runoff are also a concern.

- A plan facilitates a coordinated response. The existence of the Rapid Response Contingency Plan enabled DAR and its partners to respond to the black band coral disease in an organized manner. Some diseases move quickly and can cover large areas, so it is good to be prepared and to know what resources are available to respond to these events.

- Community involvement is key. The citizen science network Eyes of the Reef is able to recognize coral disease outbreaks more quickly than if DAR staff had been working alone. In this case, community members expanded the capacity of managers to monitor for coral disease disturbances and will play a key role in the reef’s recovery.

- Communication is critical when responding to this type of disturbance. Having a communication plan or involving a communication expert from the beginning would have aided the team in informing all partners and the community on Kauaʻi of what was known about the coral disease and about the research being done.

- Contingency funding continues to be a substantial barrier. It is difficult because when, where, and how much funding will be needed for a disease event cannot be predicted. A finance plan needs to be created that will allow funds to be isolated specifically for coral disease, bleaching, and COTS disturbances.

- Partnerships are essential. Investigating a coral disease takes a multi-disciplinary team of scientists, managers, NGOs, communication experts, community leaders, private sector participants, etc. Collaboration can allow more resources to be leveraged in a timely and efficient way during a coral disease disturbance. DAR is a member of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force and attends the task force meetings with other coral reef disease experts and managers who collaborate to plan appropriate responses to outbreaks.

DAR staff teaching a local summer camp about coral health. Photo © Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources

Funding summary

Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) and Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation (DOBOR), The School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), University of Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), US Geological Survey (USGS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Ecosystem Division (NOAA-CRED), Several additional community partners also contributed resources and supplies

Lead organizations (Management Response Team Members)

Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Aquatic Resources

University of Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, Coral Reef Ecosystem Division

The Environmental Protection Agency, Pacific Island Region

U.S. Geological Survey Wildlife Health Center

University of Hawaiʻi Kewalo Marine Laboratory

University of Hawaiʻi Department of Microbiology

Partners

Bubbles Below

Eyes of the Reef

Hanalei Watershed Hui

Kauaʻi Community College

Seasport Divers

Waipa Foundation

Resources

Reef Response: Black Band Coral Disease On Kauaʻi

Eyes of the Reef Network

Reefology 101, Coral Health and Ecology Forum

State of Hawaii Coral Reef Strategy

Written by: Anne Rosinski, Marine Resource Specialist, Division of Aquatic Resources, Hawaiʻi Department of Land & Natural Resources

Makaʻala Kaʻaumoana, Hanalei Watershed Hui

This case study was adapted from: Cullman, G. (ed.) 2014. Resilience Sourcebook: Case studies of social-ecological resilience in island systems. Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.