MPA Finance Mechanisms

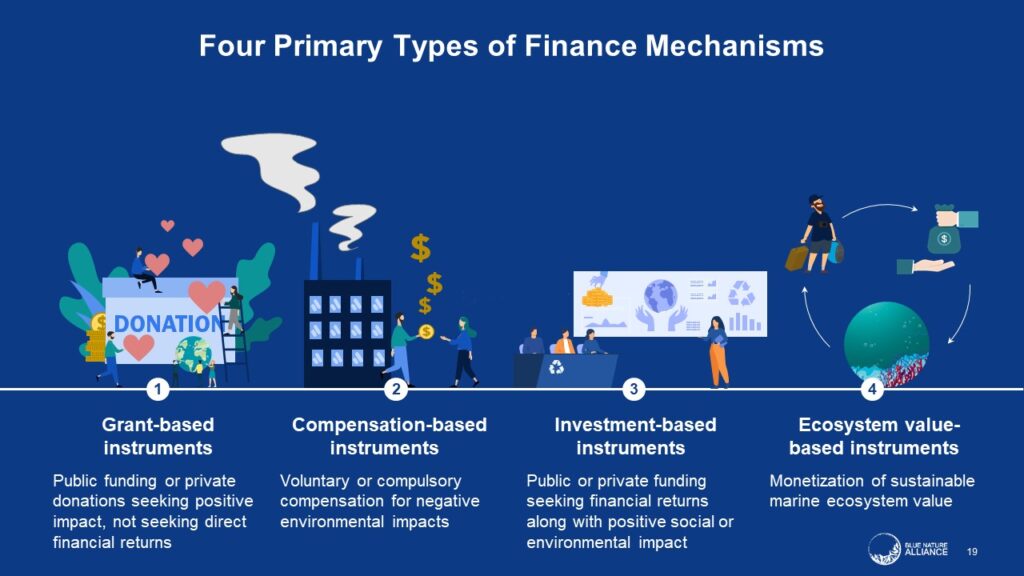

This toolkit groups potential MPA finance mechanisms into four primary types:

- Grant-Based Instruments

- Compensation-Based Instruments

- Investment-Based Instruments

- Ecosystem Value-Based Instruments

Please note: the terms "mechanism" and "instrument" are used interchangeably in this toolkit.

Primary types of finance instruments most appropriate for marine protected areas. Source: Blue Nature Alliance

Some funding instruments can be enacted by managers, but others must occur through the national or regional government. It may make sense to think about funding for a single MPA (what this toolkit calls the "site level") or funding for a network of protected areas (what this toolkit refers to as the "system level"). Often, it will be a combination of efforts at both the managerial and governmental levels that will secure funding at both the site and system levels. Based on multiple sources from 2003 to 2015, about half of MPAs, particularly in developed nations, rely on government (local, regional, and national) allocations for at least half of their funding. ref

The suitability of each finance instrument will depend on the size and context of the MPA as well as the MPA’s growth stage (e.g., Is the MPA just getting started? Is it actively growing, or is it mature or stable? Is the MPA's funding in decline or in need of reconsideration?). For more information on determining what tools and strategies will work for a particular site or system in your local context, please refer to the Prioritizing Finance Mechanisms page of this toolkit.

Grant-Based Instruments

The table below lists several common grant-based finance instruments for MPAs, along with key points about enabling conditions for implementation and other considerations to have in mind when evaluating each instrument.

click each instrument name for a brief description of that instrument

| GRANT-BASED INSTRUMENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Enabling Conditions | Additional Considerations | |

| Government Allocations |

|

|

|

| Example: United States Announces $508 Million to Protect Our Ocean | |||

| Official Development Assistance |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: OECD's explainer page on ODAs | |||

| Philanthropic Grants |

|

|

|

| Example: The Nature Conservancy Launches New Grant Program Across Northern Appalachian States | |||

| Crowdfunding |

|

|

|

| Example: Island Nation Sets Up World’s First Crowdfunded Marine Protected Area | |||

Compensation-Based Instruments

Compensation-based financing instruments can be either voluntary or compulsory, but are typically designed to offset negative environmental impacts. The table below lists several common compensation-based finance instruments for MPAs, along with key points about necessary preconditions for implementation and other considerations to have in mind when considering each instrument.

click each instrument name for a brief description of that instrument

| COMPENSATION-BASED INSTRUMENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Enabling Conditions | Additional Considerations | |

| Eco-Taxes |

|

|

|

| Example: Canada's Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act: 2020 Annual Report | |||

| Extractive Fees, Royalties, and Permits |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: Millage, K., et al. "Self-financed marine protected areas." Environmental Research Letters 16.12 (2021): 125001. | |||

| Blue Carbon Offsets |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: For more information about blue carbon, including examples of blue carbon projects, please visit the RRN Blue Carbon Toolkit | |||

| Biodiversity Offsets |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: IUCN Issues Brief: Biodiversity Offsets | |||

Investment-Based Instruments

Investment-based financing instruments are public or private funding seeking financial returns along with positive social or environmental impact. The table below lists several common investment-based finance instruments for MPAs, along with key points about necessary preconditions for implementation and other considerations to have in mind when considering each instrument.

click each instrument name for a brief description of that instrument

| INVESTMENT-BASED INSTRUMENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Enabling Conditions | Additional Considerations | |

| Blue Bonds |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: The Asian Development Bank's "Bonds to Finance the Sustainable Blue Economy: A Practitioner's Guide" | |||

| Blended Finance Funds |

|

|

|

| Example: Impact investment firm Mirova's Althelia Sustainable Ocean Fund (SOF) | |||

| Public-Private Partnerships |

|

|

|

| Example: Blue Alliance co-manages several MPAs in different parts of the world with national, provincial, and local governments, including executing strategies, business modeling, and generating blended financing. | |||

| Debt-for-Nature Swaps |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: The Debt-for-Nature Lifeline, by John Antonio Briceño, Prime Minister of Belize, and Jennifer Morris, CEO of The Nature Conservancy | |||

Examples: Utilizing Investment-Based Instruments to Finance MPAs in the Western Indian Ocean

In the following video, Dr. Fahd Al-Guthmy, Programme Director for Conservation Finance, Wildlife Conservation Society, describes the Global Fund for Coral Reefs and the Miamba Yetu Programme for sustainable reef investments, a blended finance solution that addresses the drivers of coral reef degradation.

In the following video, Alain de Comarmond, Fundraising & Partnership Manager for SeyCCAT, discusses the debt-for-nature swap and blue finance experience in The Seychelles. The planning process for this US$21.6 million debt restructuring took over six years to happen and involved many partners from the government, NGO, and finance sectors, but unlocked several 20-year-long cash flows to enable The Seychelles' marine spatial planning policy and the protection of at least 30% of its marine area.

Ecosystem Value-Based Instruments

Ecosystem value-based financing instruments involve putting a price on the value of healthy marine ecosystems. The table below lists several common ecosystem value-based finance instruments for MPAs, along with key points about necessary preconditions for implementation and other considerations to have in mind when considering each instrument.

click each instrument name for a brief description of that instrument

| ECOSYSTEM VALUE-BASED INSTRUMENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Enabling Conditions | Additional Considerations | |

| Levies on Sustainable Use |

|

|

|

| Example: Financing Protected Areas in Palau | |||

| Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) |

|

|

|

| Further Reading: Mohammed, E. Y. Payments for coastal and marine ecosystem services: prospects and principles. (2012). | |||

| Parametric Insurance |

|

|

|

| Example: In 2022, TNC announced the first-ever coral reef insurance policy in the United States, which will provide funding for rapid coral reef repair and restoration across Hawai‘i immediately following hurricane or tropical storm damage. | |||

| Nature Credits |

|

|

|

| Example: Australia’s Reef Credit Scheme rewards land managers for improving water quality (through sediment, nutrient, and/or pesticide retention) with “Reef Credits,” which are tradeable units with set values that are then sold to parties (e.g., industry, philanthropists, or the government) seeking to invest in water quality or offset their own impacts. | |||

The MPA Finance Toolkit was developed in partnership with the Blue Nature Alliance, a global partnership to catalyze effective large-scale ocean conservation. In September 2023, the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association and Blue Nature Alliance co-hosted an MPA finance workshop with marine managers in the Western Indian Ocean region. The resources presented in this toolkit were developed for and piloted by the managers in attendance.