Protecting Reef Grazers to Enable Coral Reef Recovery in Belize

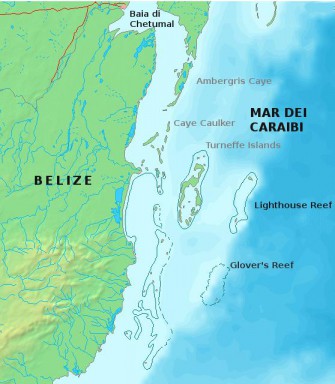

Location

Belize Barrier Reef System, Belize

The challenge

Belize is well known for its incredible biodiversity, both terrestrial and marine. Its reefs have long been considered some of the Caribbean’s most pristine and unique reefs, however they started to show worrying signs of damage at the turn of this century. A 2006 survey of 140 reefs throughout Belize found that live coral cover had declined from approximately 30% in 1995 to an average of 11%. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which has been working in Belize since the 1980s to help conserve the country’s marine environment, carries out research on the health of Belize’s fisheries from their Marine Reserve Station at Glover’s Reef.

Glover’s Reef is located within the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, where fishing, as well as spearfishing, is allowed. WCS found that groupers and some snappers are now overfished and that the proportion of parrotfish in the catch doubled between 2004 and 2008 because parrotfish are considered by fishermen as “the next best fish” to harvest.

The fact that fishermen were targeting reef-grazing species was a serious problem with far-reaching effects for the health of Belize’s reefs. Reef-grazers such as parrotfish play a critical ecological role within coral reefs; by eating large amounts of algae, they keep its growth in check, making sure that it does not overgrow the reef. Algae can smother corals, stunt their growth, and reduce their recruitment success.

Rainbow parrotfish (Scarus guacamaia), the largest herbivorous fish in the Caribbean. Photo © Julio Maaz/WCS

The health of reefs is therefore closely linked to the presence of herbivorous fish such as parrotfish. As fishermen in Belize continued to harvest parrotfish, their numbers started to rapidly decline. Research on the change in fish communities after a seven-year period (2002-2009) of fishing in Belize showed a 41% decline in parrotfish over that time period. Overfishing parrotfish already has had observable effects on Belize’s reefs. One study found that an atoll reef lagoon at Glover’s Reef that had once been very healthy with 75% coral cover now has less than 20% coral cover because of algae over-growth.

Actions taken

The traditional management option to help overfished species recover has typically been fishing closures. However, WCS conducted a 14-year study at Glover’s Reef and found that while a fishing ban in the Conservation Zone of the marine reserve was effective in helping predatory species such as barracudas and snappers recover, it had little effect on the recovery of herbivorous species. This meant that a fishing ban would not be enough to reduce the growth of algae and help corals recover. This information, along with recent information on the poor health of Belize’s reefs, helped stakeholders understand the need for an alternative and more innovative way to protect Belize’s reefs: protect major reef grazers. It was local fishermen who first voluntarily recommended a ban on fishing parrotfish after it was made clear to them how important these fish were to the health of the reef and therefore to their livelihoods. In April 2009, the voluntary ban on the fishing of parrotfish became national law when the government of Belize passed the 2009 Fisheries Regulations 2009 to protect overfished species. The 2020 Fisheries Resources Act added new regulations to those established in 2009.

The 2009 regulations prohibited any taking of parrotfish and surgeonfish in Belize’s waters. Both species are major reef-grazers, so the law directly addressed increases in catch of herbivorous fish and the negative impact this was having on reef health. By giving parrotfish and surgeonfish full protection, the hope was to help their numbers recover and to in turn reduce the growth of macroalgae threatening Belize’s reefs. Belize was the first country to pass a national law to protect reef grazers, which are critical to the health of coral reefs. In fact, many considered this law a new standard for coral reef protection, as management strategies up until then had mainly focused on marine protected areas (MPAs). Of course, enforcement and compliance is key to ensuring the success of this national-level ban, as is the prevention of legal access to international export markets for these products. WCS provided technical aid to the Belize Fisheries Department to ensure that fisheries officers and patrols enforced the law.

Dr. Peter Mumby explains the importance of parrotfish as grazers maintaining the health of coral reefs to a large group of fishermen in Belize City. Photo © WCS

A second set of regulations helped protect the endangered Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus), listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Fishing of the Nassau Grouper became heavily regulated – with minimum and maximum size limits, and all groupers must be brought in whole so that catch rates can be monitored. Additionally, spawning aggregations of Nassau grouper are protected, and spearfishing is banned within marine reserves. A third set of regulations creates a number of “no-take” zones in protected areas, which are closed to fishing. The areas selected are biodiversity hotspots with unique and/or fragile ecosystems and/or species.

As of 2022, the focus on reef conservation is shifting towards digital enforcement innovations and improvement of access to higher value markets for Belize’s legal fisheries (lobster and conch on the international market, other finfish species on the domestic market). The Ministry of Blue Economy and Civil Aviation is promoting the improved ecological and socioeconomic sustainability of all marine economic activities. Focusing on individual species as a conservation approach, while valuable, will likely begin to be expressed more in the wider context of additional objectives of the Ministry for marine economic activities at a holistic level.

How successful has it been?

There is some strong evidence that the fishing ban is helping reef-grazers recover. In 2011, the herbivore biomass in Belize surpassed levels recorded in 2006 and increased 33% above the low levels measured in 2009. This increase in herbivore biomass should in time translate to a decrease in algae dominance in Belize’s reefs.

The effectiveness of the fishing ban in restoring fish populations and coral assemblages in Belize was evaluated in a study between 2009 and 2011. Increases in herbivorous fish biomass were found at approximately half of the studied sites, but coral and macroalgal cover stayed the same. However, the authors of the study attribute the lack of change in coral and algae cover to how recent the ban on fishing reef-grazers was.

Stoplight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) with blue tangs, which are also protected grazers. Photo © Virginia Burns/WCS

Enforcement efforts appear to be successful as there have been very few instances of illegal catch of parrotfish since the ban was introduced. The results of a 2012 genetic study of fillet samples throughout Belize also demonstrate very good compliance with the ban – over 90% of the fillets checked were not parrotfish.

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Fishermen are key stakeholders in marine conservation. Incorporating fishers’ tradition ecological knowledge of and perspectives on fisheries and reefs into conservation and management plans is critical to ensuring the success of the conservation plans and also to ensuring that the management plans serve both the needs of the communities, as well as the species or areas being targeted for conservation.

- Extensive research on the subject at hand (in this case, the link between parrotfish density and reef health) is essential to making informed decisions. Additionally, finding ways to separate this from other potential causes of reef health decline such as seawater temperature, ocean acidification, arrival of lionfish in the Caribbean, hurricanes, pandemics leading to economic hardship for fishers, and other potential threats is extremely important.

- Involve fishers directly in the design and implementation of research and monitoring so they are part of the processes that lead to research outputs and decision-making.

- Reef recovery takes time – although data indicate an increase in biomass of parrotfishes, slow-growing corals need long-term protection to fully recover.

Funding summary

The monitoring and fisheries catch data collection programs of WCS have been carried out for many years in partnership with the Fisheries Department, and they will continue in an effort to record the recovery of parrotfish at Glover’s Reef and track the health of the coral reef. This work was funded primarily by the Oak Foundation, USAID, and the Summit Foundation.

Lead organizations

Wildlife Conservation Society

Belize Fisheries Department

Resources

Belize Takes Action to Save Coral Reefs & Fisheries, Wildlife Conservation Society

Belize Limits Reef Fishing, Wildlife Conservation Society

Belize protected area boosting predatory fish populations, Wildlife Conservation Society

Fishing down a Caribbean food web relaxes trophic cascades

Testing for top-down control: can post-disturbance fisheries closures reverse algal dominance