Sustainable Financing

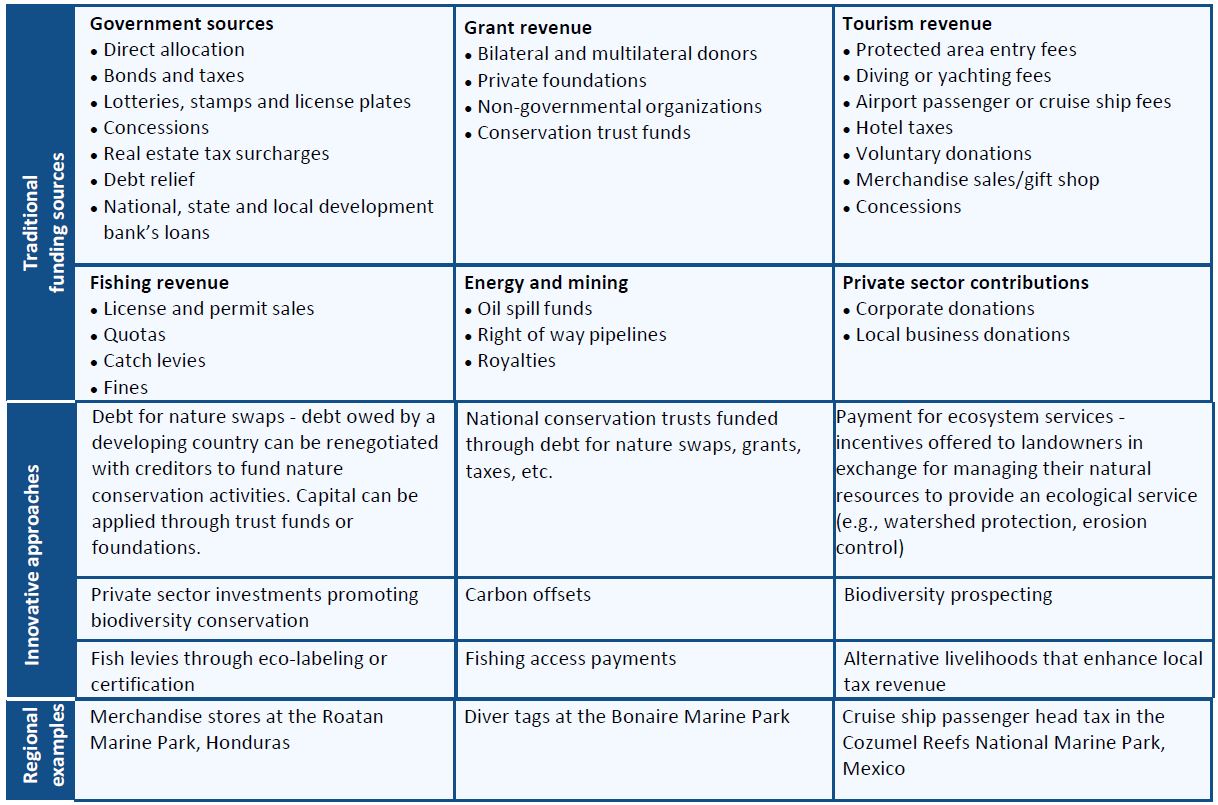

(Source: Adapted from Spergel and Moye 2004, Gallegos et al. 2005, and CBD 2012).

A key goal is to identify solutions that generate revenue for reef restoration, and also support other community and social benefits as well. For a detailed analysis of external funding sources including pros and cons and case studies, see Protecting Our Marine Treasures. While these were developed specifically for marine protected areas, they are relevant for reef restoration as well.

Assessing the Feasibility of Conservation Finance

Financing mechanisms should be evaluated as part of a financing strategy for conservation and restoration programs. A financial assessment considers the project’s scope, spatial scale, strategic activities and time frame, as well as total costs, current sources of revenue, and gaps. A sustainable financing strategy evaluates the total funding available from all sources — government budgets; funding from private donors, corporate or NGO partners; revenue generated by access and user fees, fines, and other payment schemes. The assessment estimates the funding needed and determines the financing gap that must be filled to meet the program’s conservation or restoration goals. A financial assessment then evaluates the legal, administrative, social, political, and environmental context to determine the most appropriate finance mechanisms (see the Guide to Conservation Finance).

Six steps to develop and maintain a sustainable finance plan (see Sustainable Financing: Lessons Learned for Building and Sustaining Effective Marine Protected Areas):

- Determine your funding needs and shortfalls

- Review the efficiency and effectiveness of your current administrative system in achieving management goals

- Assess the socioeconomic costs and benefits of management

- Identify real and potential funding sources

- Develop a business and finance plan that delivers a combination of reduced costs through improved management efficiency and/or increased revenue from new or potential funding sources

- Map out implementation steps and methods for monitoring progress.

As noted above, innovative sustainable financing mechanisms are being developed including raising conservation and restoration funds from new markets (e.g., carbon offsets, water, or other payments for ecosystem services). Actions to improve policy and market conditions (e.g., reforming environmentally-harmful subsidies and creating positive incentives) are important to support broader conservation efforts. Efforts to devolve management and funding responsibilities to local communities and businesses, and share the costs and benefits of environmental protection with local stakeholders (e.g., communities and private landholders) are increasingly implemented to support sustainable financing of natural ecosystems.

One new area of sustainable financing for reef restoration is through the development of reef insurance mechanisms. A client (e.g., hotel association or government entity) buys an insurance policy to restore the reef following a major hurricane/cyclone impact. Swiss Re, a global provider of reinsurance, insurance and other insurance-based forms of risk transfer, partnered with The Nature Conservancy, local businesses and the State government of Quintana Roo in Mexico to develop a trust fund (the Coastal Zone Management Trust) and insurance policy for the reef. The fund collects a portion of a local tourist tax to pay for beach and reef maintenance plus the purchase of an insurance cover to protect against severe hurricanes. The pilot project designed a parametric insurance cover for a 40 mile (60 km) stretch of beach and reef between Cancun and Puerto Morelos. When storms occur over a certain threshold, payouts will be used for restoration of the reef. The parametric approach was chosen because it has a very quick payout mechanism meaning that funds are made available in a matter of days. This is essential because the funds are required to cover the costs of clearing the reef of debris immediately after the storm and to collect broken coral for later restoration purposes. Protocols for these post-disaster activities and training for “brigades” to conduct the work were developed by The Nature Conservancy. The project represents the first time that a natural resource has been insured for the protective value it provides to the local community and tourist economy, and is a model for similar products linking the protection of nature to payouts following disaster.

Another area of innovative finance that is being explored is resilience insurance. This combines traditional coverage against storm losses with an investment in resilience (e.g., planting mangroves, restoring coral reefs). If the ‘resilience’ investment is successfully implemented, within the insurance treaty term (i.e., when the policy premium is being paid), then the premium related to the risk reduction is used to cover the cost of the ‘resilience’ investment. There is no successful example for a ‘resilience’ insurance solution that involves nature-based solutions, however the MyStrongHome program is an example of where roofing upgrades (to wind-proof against hurricanes) are paid through traditional homeowners insurance. Conservation organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy, are working with insurance and reinsurance companies to explore whether insurance premiums could be reduced for companies/individuals that protect reefs and coastal wetlands, or upstream forests, just as rates are reduced for flood barriers and hurricane shelters.

Sustainable Restoration through Tourism

New collaborations are being explored to create new sustainable financing opportunities to support coral reef restoration efforts through the tourism sector. The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Division has developed several resources to promote successful coral reef restoration through sustainable tourism operations and practices, including the REEFhabilitation Experience – a hands-on learning adventure for tourists to actively participate in coral restoration. REEFhabilitation is designed to be a marketable experience for tourists and provide sustainable funding to ongoing restoration projects, while providing tourists with opportunities to participate in restoration activities and promote coral reef awareness. To access materials describing this experience, see the Sustainable Tourism – Diversifying Livelihoods webpage.

New collaborations are being explored to create new sustainable financing opportunities to support coral reef restoration efforts through the tourism sector. The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Division has developed several resources to promote successful coral reef restoration through sustainable tourism operations and practices, including the REEFhabilitation Experience – a hands-on learning adventure for tourists to actively participate in coral restoration. REEFhabilitation is designed to be a marketable experience for tourists and provide sustainable funding to ongoing restoration projects, while providing tourists with opportunities to participate in restoration activities and promote coral reef awareness. To access materials describing this experience, see the Sustainable Tourism – Diversifying Livelihoods webpage.

Resources

Marine Conservation Finance: The Need for and Scope of an Emerging Field

Overview of Sustainable Financing Mechanisms from the Convention on Biological Diversity

Investing in Conservation: A Landscape Assessment of an Emerging Market

The International Guidebook of Environmental Finance Tools

Additional reports highlighting private sector conservation finance